- April 1, 2024

Kyoung Ryul Lee, MD, PhD, CEO of the SCL Group, Seoul Clinical Laboratory, a Specialist in Laboratory Medicine

Kyoung Ryul Lee, MD, PhD, CEO of the SCL Group, Seoul Clinical Laboratory, a Specialist in Laboratory Medicine What motivated your decision to attend medical school and become a physician? Could you share some particularly

- August 5, 2024

ISSUE 28

FROM THE PUBLISHER W elcome to the 28th edition of the World Asian Medical Journal. This issue encompasses a captivating cover story featuring an interview with Dr. Huang, a distinguished medical professional whose journey from

- August 5, 2024

Youngmee Jee, MD, PhD | Inspirational Asian Healthcare Leader

INSPIRATIONAL ASIAN HEALTHCARE LEADER Youngmee Jee, MD, PhD Commissioner of Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency INTERVIEW 01 Tell us how you decided to pursue a career in medicine. How did you choose your specialty?

- September 21, 2024

Rethinking Hypothyroidism

Rethinking Hypothyroidism: Why Treatment Must Change and What Patients Can Do Author: Antonio C. Bianco, MD Translated by: Semin Kim, MD & Sihoon Lee, MD About the book “Rethinking Hypothyroidism” The limitations of current

- October 1, 2024

The Internet of Things (Revision 2021)

Purchase LinkThe Internet of Things (Revision 2021) Author: Sam Greengard We turn on the lights in our house from a desk in an office miles away. Our refrigerator alerts us to buy milk on the

- October 1, 2024

Superconvergence

Purchase LinkSuperconvergence Author: Jamie Metzl In Superconvergence, leading futurist and OneShared World founder Jamie Metzl explores how artificial intelligence, genome sequencing, gene editing, and other revolutionary technologies are transforming our lives, world, and future. These

- October 12, 2024

The Strategic Importance of Location in the U.S. for Foreign Bio and Pharma Companies

The Strategic Importance of Location in the U.S. for Foreign Bio and Pharma Companies DoHyun Cho, PhD (CEO, W Medical Strategy Group) The U.S. Market: A Cornerstone of Global Expansion For pharmaceutical and biotech companies,

- October 12, 2024

South Korea’s Healthcare Crisis: Beyond the Numbers

South Korea’s Healthcare Crisis: Beyond the Numbers Dongju Shin, Dong-Jin Shin INTRODUCTION The South Korean healthcare system has recently plunged into a significant crisis following a February 2024 announcement by the government to increase medical

- October 14, 2024

Overcoming Disparities in Gastric Cancer Care

Overcoming Disparities in Gastric Cancer Care Chul S. Hyun, MD, PhD, MPH Gastric Cancer and Prevention Screening Program, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide,

- October 15, 2024

The Global OR – An Introduction to Global Surgery

The Global OR – An Introduction to Global Surgery Kee B. Park, MD, MPH, Dawn Poh, MBBS, MRes Introduction An estimated 5 billion people worldwide lack access to timely, affordable, and safe surgical care, including

- February 1, 2026

- COVER STORY

Medical Education Beyond the Classroom:

A Physician Shaped by Practice, Service, and Mentorship,

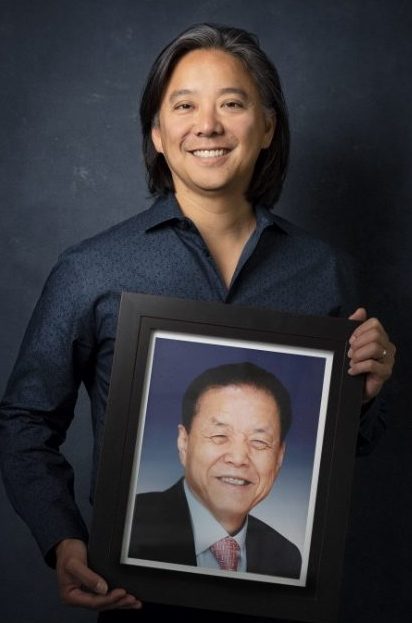

Paul C. Kang, MD

When we think of medical education, the default image is often institutional: deans, presidents, endowed professors, lecture halls, accreditation standards, and curricula carefully mapped across years of training. These figures and structures matter deeply. They shape the scaffolding of medicine and ensure rigor, continuity, and standards across generations of physicians.

But education in medicine does not end at the classroom door—and in many ways, it does not truly begin there either.

At NexBioHealth, we believe that the most formative medical education often happens outside formal titles and beyond institutional boundaries. It happens in clinics built from scratch, in communities with limited resources, in moments of moral decision-making, and in the lived tension between innovation, responsibility, faith, and service. It happens when physicians translate what they have learned into systems that endure—and when they teach not by instruction alone, but by example.

That is why, for this issue dedicated to Medical Education, we are featuring Paul C. Kang, MD.

Dr. Kang is not a university president or a career dean. Yet his life’s work represents a powerful and underrecognized form of medical education: education embodied. Through decades of private practice leadership, global mission work, mentorship, and now academic service, he has demonstrated how physicians learn—and teach—what cannot be codified in syllabi: judgment, humility, resilience, stewardship, and purpose. His work reminds us that medicine is not only a body of knowledge to be mastered, but a responsibility to be carried.

In communities from Washington, DC to Roatán, Honduras, Dr. Kang has shown how technical excellence, systems thinking, and moral clarity can coexist—and how the lessons learned at the bedside, in the operating room, and in resource-limited settings shape physicians long after formal training ends. In doing so, he exemplifies a broader vision of medical education: one rooted in lived experience, mentorship across generations, and the courage to apply knowledge where it matters most.

This issue invites readers to expand their understanding of what it means to educate physicians—and to recognize that some of the most enduring teachers in medicine are those who lead not from podiums, but from practice, service, and example.

I. Origins & Family

Your journey into medicine is deeply shaped by your father, who lost his vision at a young age yet went on to achieve remarkable things. What was it like growing up under his influence, and what lessons from his life still guide you today?

Growing up with a blind father, I always felt a quiet desire to understand his condition—and, if possible, help fix it. That instinct eventually drew me toward ophthalmology. But my father, Young Woo Kang, influenced me in ways that go far beyond my specialty choice. He shaped how I think about ability, resilience, and what it really means to care for others.

My father was born in South Korea in 1944 and lost his vision at sixteen after a soccer accident. With limited access to medical care, his blindness became permanent. He later became an orphan and grew up in poverty. At the time, discrimination against people with disabilities in Korea—especially the blind—was widespread. Many believed that encountering a blind person brought bad luck. Education was off-limits, and job opportunities were essentially restricted to fortune telling or massage.

My father was born in South Korea in 1944 and lost his vision at sixteen after a soccer accident. With limited access to medical care, his blindness became permanent. He later became an orphan and grew up in poverty. At the time, discrimination against people with disabilities in Korea—especially the blind—was widespread. Many believed that encountering a blind person brought bad luck. Education was off-limits, and job opportunities were essentially restricted to fortune telling or massage.

Despite all of this, my father refused to accept those limitations. He became the first blind Korean to attend college and eventually earned a doctorate degree. He went on to teach as a college professor, serve under several U.S. presidents on the National Council on Disability, and help establish Goodwill Industries in Korea. His story has been told in books and films, but for me, it was simply the example I grew up with every day.

One formative memory comes from when I was in fourth grade, traveling alone with my father from Chicago to Louisville. We navigated buses, hotels, and meals together as a team. Even at a young age, I appreciated the responsibility and skill required to be a guide for my father—calling out curbs at street crossings, describing the layout of a room, or letting him know where food and drinks were on the table. It taught me to communicate clearly, notice details others overlook, and anticipate needs. Looking back, those moments quietly trained skills I rely on as a physician today.

At the same time, my father was one of the most capable people I knew. He taught me how to “see” without eyes—how to look beyond physical limitations and recognize human worth. Through him, I learned that insight often comes from unexpected places and that resilience can redefine what is possible. He taught me lessons of life that I could have only learned through his perspective.

My father was also a deeply devout Christian, and his faith shaped how he understood both suffering and purpose. He believed that setbacks—his blindness included—were often part of a much larger story. He once told me that knowing what he believed to be the ultimate outcome of his life, he would not trade his blindness for the ability to see. That perspective stayed with me.

Growing up with him gave me a lens I carry into every part of my life. It influences how I counsel patients facing uncertainty or loss, how I approach my career with humility and gratitude, and how I try to be present for my family. Watching my father live with faith, meaning, and joy—despite circumstances most people would see only as limitation—taught me that healing isn’t always about restoring what was lost, but about helping people find purpose, hope, and dignity where they are.

When I felt uncertain about my future, my father would remind me, “I am a blind man in a foreign country. If I can accomplish this much, imagine what you can do.” That message still stays with me. It set a high bar for my own expectations, a responsibility to help those who face barriers, and a steady determination to meet challenges with purpose and compassion.

II. Becoming a Physician

When you first entered medicine, what did you imagine your career would look like? How did your understanding of what it means to be a physician evolve once you were in practice?

When I first entered medicine, I imagined a career focused on technical excellence—mastering procedures, using the latest technology, and delivering the best possible visual outcomes for my patients. As an ophthalmologist, I was quickly drawn to cornea, cataract, and refractive surgery. I loved that this subspecialty allowed me to not just slow vision loss, but often to restore or enhance vision. The pace of innovation—lasers, intraocular lenses, and constantly evolving surgical techniques—was energizing.

When I first entered medicine, I imagined a career focused on technical excellence—mastering procedures, using the latest technology, and delivering the best possible visual outcomes for my patients. As an ophthalmologist, I was quickly drawn to cornea, cataract, and refractive surgery. I loved that this subspecialty allowed me to not just slow vision loss, but often to restore or enhance vision. The pace of innovation—lasers, intraocular lenses, and constantly evolving surgical techniques—was energizing.

My early career goal was straightforward: provide outstanding care by using the most advanced tools and strategies available. I believed the best environment for that was private practice. While academic medicine plays an important role, it felt weighed down by bureaucracy and politics. In a fast- moving field like ophthalmology, layers of committees, meetings, and approval processes often seemed more like obstacles than safeguards.

Private practice gave me autonomy. I could make decisions quickly, become an early adopter of new technology, and build systems that supported high- quality care. I valued the ability to assemble the right team—colleagues, technicians, and staff who shared a commitment to excellence—and to implement best practices efficiently.

What I didn’t fully anticipate was how much being a physician extended beyond medicine itself. I quickly learned that success required fluency in areas rarely taught during training: business operations, accounting, human resources, compliance, billing, and coding. At times, the learning curve felt overwhelming, but it was also deeply rewarding. I came to realize that running a well-managed practice isn’t separate from patient care—it’s essential to it. Those skills allowed me to integrate new technologies, expand to satellite offices and surgery centers, and build a practice trusted by both patients and the broader community.

I also discovered that my career could extend beyond traditional patient care. Over time, I became the team ophthalmologist for several professional sports teams in the Washington, DC area and participated in multiple clinical trials evaluating new treatment options. These experiences broadened my perspective and reinforced the importance of collaboration, innovation, and adaptability in medicine.

Perhaps the biggest evolution in my understanding of what it means to be a physician is realizing that learning never ends—but neither can work consume everything else. Early on, success meant volume, growth, and technical mastery. Today, I define it more

holistically: delivering excellent care while building a sustainable career that leaves room for family, reflection, and personal well-being. Every physician must think like a clinician-scientist—constantly questioning, refining, and improving how we care for patients—while also recognizing the importance of balance. Striving for mastery with humility, staying curious as medicine evolves, and protecting longevity in the profession have become just as important as innovation itself. That pursuit, I’ve learned, is never- ending—and that’s what makes the profession so compelling.

III. Redefining Success in Medicine

You built a highly successful private practice before shifting more of your time toward academia, mentorship, and service. Tell us about your practice. What prompted that transition, and how has your definition of “success” in medicine changed over time?

When I look back on my career, I see it unfolding in distinct seasons, each shaping how I define success in medicine. Early on, success meant building something excellent—technically, clinically, and operationally. For seventeen years, I practiced at the Eye Doctors of Washington in Washington, DC, with a simple but ambitious goal: to integrate the best technology and strategies to deliver the best possible outcomes for our patients. We built the practice around innovation, becoming the first in the region to offer all-laser LASIK, laser cataract surgery, and premium intraocular lenses—not for novelty’s sake, but because these advances allowed us to restore vision in ways that were previously impossible. As the practice grew, so did its scope and reputation. We expanded services and locations, earned national recognition, served as team physicians for professional sports teams, and I became deeply involved in leadership, professional societies, and clinical trials. There was an undeniable exhilaration in building something so successful.

With that growth, however, came complexity. Managing a large practice became increasingly demanding, and as senior partners approached retirement, succession planning became essential. When the practice attracted interest from private equity, we made the decision to sell—creating a natural inflection point that offered continuity for the group and freedom from day-to-day management. At the same time, I carried a persistent desire to serve patients like my father—those without access to advanced care. I realized, ironically, that the technologies I valued most would have been completely inaccessible to someone like him growing up blind in Korea. That tension came into sharp focus when I discovered Health In Sight Mission in Roatan, Honduras. The contrast between the resources of my practice in Washington, DC and the realities of care in Roatan—limited infrastructure, power outages, and improvised solutions—was impossible to ignore. Standing in that clinic, I felt called to apply what I had learned about building practices, integrating technology, and partnering with industry to create sustainable eye care where it was most needed.

The COVID-19 pandemic deepened that reflection. During that time, my longtime surgical coordinator and close colleague passed away, and I was struck by how differently well-resourced communities would weather the crisis compared to places like Roatan. It became clear to me that Washington, DC would be fine without me—but Roatan needed sustained service. After selling my practice, my family and I moved to Connecticut, taking a leap of faith without a clear plan. Months later, an opportunity at Yale unexpectedly emerged, offering the chance to teach, care for patients, and continue my commitment to mission work. Today, my definition of success has evolved. It is no longer measured by growth, volume, or innovation alone, but by impact—training the next generation, expanding access to care, building sustainable systems, and doing work aligned with my values while leaving room for family and balance.

IV. Mission Work & Global Perspective

Health In Sight Mission has become central to your work. What drew you to this mission, and what has practicing medicine in resource-limited settings taught you that clinical training alone could not?

Health In Sight Mission has become central to my work because it brings together accessibility, sustainability, and purpose in a way I had never experienced before. Roatan, an island off the coast of Honduras best known for cruise ships and scuba diving, exists alongside profound poverty and historically limited access to healthcare—particularly comprehensive eye care. Health In Sight Mission is a faith-based nonprofit founded more than twenty years ago with a commitment to Christian service and partnership with the local community. I was initially drawn to the mission because it was accessible—a relatively short trip from the U.S.—and because it allowed physicians to serve alongside their families in a safe, structured environment. What I didn’t anticipate was how deeply it would reshape my understanding of medicine and give new meaning to the skills I had developed over years in private practice.

Health In Sight Mission has become central to my work because it brings together accessibility, sustainability, and purpose in a way I had never experienced before. Roatan, an island off the coast of Honduras best known for cruise ships and scuba diving, exists alongside profound poverty and historically limited access to healthcare—particularly comprehensive eye care. Health In Sight Mission is a faith-based nonprofit founded more than twenty years ago with a commitment to Christian service and partnership with the local community. I was initially drawn to the mission because it was accessible—a relatively short trip from the U.S.—and because it allowed physicians to serve alongside their families in a safe, structured environment. What I didn’t anticipate was how deeply it would reshape my understanding of medicine and give new meaning to the skills I had developed over years in private practice.

Practicing in a resource-limited setting quickly taught me that delivering care successfully requires far more than clinical skill alone. Sustainability matters. We are intentional about ensuring that our work strengthens, rather than displaces, local providers, partnering closely with Honduran ophthalmologists and community leaders to ensure continuity of care. Over time, trust became as important as technology. Drawing on lessons from private practice and long- standing industry relationships, we brought modern diagnostic equipment to the island and built a clinic with appropriate infrastructure, allowing local staff to perform testing even when visiting teams are not present. In this setting, innovation became a tool for equity—not just advancement.

This work has also transformed how physicians engage in mission medicine. Many feel called to serve but hesitate because of concerns about safety, effectiveness, or sustainability. By creating systems that support thoughtful, long-term care, we’ve been able to expand participation across multiple subspecialties and institutions while working toward a long-term goal of eliminating preventable blindness on the island. Practicing in Roatan has taught me humility, creativity, and systems thinking—lessons no formal training alone could impart. In many ways, it mirrors what I learned growing up with my father: that faith is not only about acceptance, but about having the courage to challenge barriers that stand in the way of dignity, compassion, and justice—for patients, communities, and those who serve them.

How has global service changed the way you view patients, privilege, and responsibility in your everyday medical practice back in the U.S.?

Global service has profoundly changed the way I view patients, privilege, and responsibility in my everyday medical practice in the United States. Over time, medicine can easily become routine. The demands of efficiency, protocols, documentation, and metrics are necessary for modern healthcare to function, but they can quietly pull us away from the original reason most of us chose this profession: to care for people.

In Roatan, the pace is different. Many of those external pressures fall away, and the focus returns to the patient in front of you. With far fewer resources, we still find ways to care deeply and meaningfully. Practicing with less has reminded me of what matters most. Mission work strips medicine down to its core and re-centers the human connection that first drew me to this work.

That perspective follows me home. In the U.S., clinical care can become highly algorithmic—patients seen quickly, outcomes expected to be perfect, and little margin for imperfection. We often carry the emotional weight of complications silently, while failing to pause and celebrate good outcomes. Over time, the beauty and humanity of medicine can be replaced by pressure and fatigue.

Serving in resource-limited settings has reminded me that medicine is not only about outcomes, but about presence. Even when we cannot fix everything, patients express profound gratitude simply for being seen, heard, and cared for. That gratitude has reshaped how I approach my patients at home, encouraging me to slow down, listen more carefully, and recognize the privilege of being trusted with someone’s care.

Global service has also deepened my awareness of privilege. Many people in Roatan face daily challenges related to poverty and access to care, yet demonstrate extraordinary resilience, joy, and community. Ultimately, this work has reframed my sense of responsibility—not just as technical excellence, but as stewardship of resources, trust, and compassion. Carrying these lessons back into my everyday practice has helped me practice medicine with greater humility, gratitude, and intention, and to see each patient encounter not as a task to complete, but as a privilege to honor.

V. Mentorship & Learning Beyond the Classroom

You mentor many young physicians outside traditional academic structures. Why is mentorship so important to you at this stage of your life?

Mentorship has become increasingly important to me at this stage of my life because I’ve come to believe that careers unfold in seasons. I once heard Denzel Washington describe that arc simply: first you learn, then you earn, and eventually, you return. That idea resonates deeply with me.

I’ve been fortunate to have a wide range of professional experiences, but I didn’t come from a family of physicians. Much of what I learned came through trial and error—through successes, setbacks, and moments of real uncertainty. My career was not a straight upward trajectory. Every opportunity carried risk, responsibility, and the pressure of knowing that patients and their families were depending on me. Looking back, there are many moments when having a trusted mentor—someone to offer perspective or reassurance—would have made a meaningful difference.

In a relatively short period of time, I went from finishing fellowship to becoming a partner in private practice, a community leader, and an innovator in my field. At the same time, I was trying to be a supportive husband to my OB/GYN wife and a present father to our three children. I wish I had better understood earlier how to balance ambition with sustainability, and professional success with family life.

Medical training is highly structured and takes place in the insulated environment of academic institutions. While that structure is essential, it leaves little room to address the realities physicians face once training ends—career choices, leadership challenges, financial decisions, work–life balance, and the emotional weight of responsibility. That gap is where mentorship becomes critical.

Because my career has spanned private practice, academia, medical mission work, and collaboration with industry, I’m able to offer a broader perspective on what a career in medicine can look like. I find great joy in helping residents and young physicians explore possibilities they may not have considered, connecting them with opportunities, and opening doors—then watching them run through those doors on their own. At this stage of my life, mentorship feels less like guidance and more like stewardship. I’m excited to see what this next generation will build, and I’m grateful to play even a small role in helping them find their path.

Some of the most important lessons in medicine are never taught in classrooms. In your experience, where do physicians truly learn how to become doctors—and where does formal medical education fall short?

Some of the most important lessons in medicine are never taught in classrooms. In my experience, physicians truly learn how to become doctors through direct patient care. After all, it’s called medical practice for a reason. Responsibility, judgment, and the weight of decision-making cannot be fully simulated—they are learned over time, through experience, accountability, and reflection at the bedside.

Some of the most important lessons in medicine are never taught in classrooms. In my experience, physicians truly learn how to become doctors through direct patient care. After all, it’s called medical practice for a reason. Responsibility, judgment, and the weight of decision-making cannot be fully simulated—they are learned over time, through experience, accountability, and reflection at the bedside.

Formal medical education provides an essential foundation, but it is just that—a framework. I often tell trainees that there are many successful ways to practice medicine beyond the environment in which they were trained. It’s easy to assume that one’s academic institution represents the “right” or definitive way to practice, but medicine extends far beyond any single system or philosophy. Standards of care vary across cultures, countries, and belief systems. Eastern and Western medicine, cultural expectations, and even homeopathic or complementary approaches all influence how patients understand health and healing.

Medical education tends to focus heavily on diagnosis and treatment algorithms, which are important, but patient care is never purely algorithmic. True care requires attention to the whole person—physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and social well-being. Physicians must learn not to become shortsighted or overly dependent on protocols alone, but instead to draw on experience, remain open-minded, and continually reassess what is best for the individual patient in front of them.

I often use the analogy of learning a sport, like basketball. You can be taught the rules of the game and the fundamental skills needed to play, but true mastery only comes from playing over time—learning from mistakes, adapting to different opponents, and developing instincts. The best players don’t just follow the fundamentals; they innovate, create new strategies, and redefine how the game is played. Medicine is no different.

Ultimately, becoming a doctor is a lifelong process of learning—one that requires humility, curiosity, and a willingness to grow beyond formal training. The classroom teaches the basics, but experience teaches wisdom. The best physicians remain students throughout their careers, always ready to listen, learn, and evolve in service of their patients.

VI. Reflection, NexBioHealth & Looking Forward

NexBioHealth focuses on medicine beyond metrics and productivity. What resonates with you about this mission, and why do you think platforms like this matter for the culture of medicine today?

What resonates most with me about NexBioHealth is its recognition that medicine cannot be reduced to metrics, productivity, or checklists. While those measures have a place, they fail to capture the complexity of what it truly means to be a physician. Young doctors and trainees intuitively understand this. They know early on that medicine extends far beyond formal education, protocols, and performance benchmarks—but they often lack access to the lived experience and guidance needed to navigate that reality.

Early in training, decisions are largely prescribed: where to rotate, what to study, how to progress. But once physicians move beyond that structure, the questions become far more complex. What does a sustainable career look like? How do you balance ambition with family, service, and personal well-being? How do you choose among private practice, academia, industry, or nontraditional paths? These are not questions answered by exams or productivity dashboards—they are answered through conversation, mentorship, and shared experience.

We live in a time when people seek information before making even the smallest decisions. We read countless reviews before choosing a restaurant for dinner or a hotel for a vacation. Yet physicians are often expected to make life-defining career choices with remarkably little insight into what different paths actually look like day to day. Platforms like NexBioHealth help close that gap by creating access—to perspective, to mentorship, and to honest dialogue about the realities of medicine.

Equally important is the sense of community such platforms foster. Medicine can be isolating, especially as pressures around efficiency, documentation, and performance continue to grow. NexBioHealth reminds us that we are not navigating these challenges alone. We are part of a shared profession—facing similar struggles, asking similar questions, and striving for meaning in the same demanding environment. Creating spaces where physicians can learn from one another, support one another, and reflect together is essential for the health of the profession itself.

Looking back, what experiences—inside or outside medicine—shaped you most as a person and physician?

Looking back, there is no question that growing up with my blind father had the most profound impact on me—both as a person and as a physician. I’ve spoken about how his life shaped my professional path and my commitment to mission work, but his influence reaches far beyond those choices. Many of the values that guide how I live and practice medicine today were formed long before I ever put on a white coat.

Despite my later academic achievements, I was not a strong student in my early years. Studying never came easily to me, and I struggled in ways I didn’t yet understand. Only as an adult did I learn that much of this difficulty was due to undiagnosed dyslexia. At the time, however, I simply felt behind.

One memory from second grade stands out vividly. During a parent open house, my mother searched for my desk and eventually found it placed directly next to the teacher’s—isolated from the rest of the class. At first, she assumed it was an honor. She soon learned the real reason: I was seated there to keep me from talking and distracting others. While my parents were disappointed in my academic performance, they never withdrew their encouragement. In fact, they rewarded effort and behavior just as much as grades—perhaps understanding that perseverance mattered more than early success.

Standardized testing only reinforced my struggles. Year after year, I failed to score well enough to be placed in honors classes. While I occasionally wondered if I was “smart enough,” the disappointment weighed more heavily on my parents—especially my father. Having fought his own way through systemic barriers to education, he refused to accept the conclusion that I was simply “above average.” He challenged the school, pointed to my developmental milestones, and ultimately convinced them to administer an IQ test. To nearly everyone’s surprise—except his—I tested in the exceptional range. With that evidence, the school reversed course and placed me in honors classes.

In retrospect, that moment was pivotal. It was a clear example of how belief, advocacy, and family support can accomplish what talent alone sometimes cannot. My father had fought for his own education as a blind man in a society that dismissed him; now he was teaching me how to challenge systems, persist through doubt, and trust that setbacks do not define potential.

As I grew older, I learned how to adapt. Even without knowing I had dyslexia, I understood that traditional reading was difficult for me. My father helped me obtain audio versions of textbooks from libraries for the blind, which transformed how I studied. He also instilled in me a simple but powerful mantra: you never know unless you try. That belief freed me to explore widely— from sports and theater to playing guitar, writing songs, academic pursuits, and even starting a company while in college.

Perhaps the most enduring lessons came not from classrooms, but from time spent with my father outdoors. He loved walking and hiking, and on family trips to national parks, my brother and I would often hike challenging trails with him. The terrain could be steep and rocky, sometimes requiring us to crawl on hands and knees. Other hikers would stare, clearly wondering why a blind man was attempting such paths. But my father always pressed forward with calm confidence.

One hike ended at a suspension bridge—an obstacle that stopped me cold. I’ve never been comfortable with heights, and I froze. Yet in that moment, it was my blind father who urged me forward. I was supposed to be guiding him, but instead he was guiding me. In many ways, that scene captures the story of my life.

From him, I learned resilience, courage, and faith— not the absence of fear, but the willingness to move forward despite it. Those lessons continue to shape how I approach medicine, adversity, and responsibility. They remind me that true vision has little to do with what the eyes can see, and everything to do with trust, perseverance, and the people who believe in us when we struggle to believe in ourselves.

Finally, if you could speak directly to a medical student or resident who feels disillusioned or burned out, what would you want them to hear?

For the trainee who feels disillusioned or burned out, know this: what you’re experiencing is not a failure— it’s part of the journey, and you are not alone. So much of becoming a physician involves coming to terms with impossible expectations. You are asked to master an enormous and ever-changing body of knowledge, to grow confident in your skills while remaining humble enough to learn from mistakes, and to pursue perfect outcomes while knowing that complications and uncertainty are inevitable. Medicine is a noble calling, but even if you gave every waking hour, you would still fall short of every demand placed upon you. That tension is not a personal weakness—it is the reality of the profession.

For the trainee who feels disillusioned or burned out, know this: what you’re experiencing is not a failure— it’s part of the journey, and you are not alone. So much of becoming a physician involves coming to terms with impossible expectations. You are asked to master an enormous and ever-changing body of knowledge, to grow confident in your skills while remaining humble enough to learn from mistakes, and to pursue perfect outcomes while knowing that complications and uncertainty are inevitable. Medicine is a noble calling, but even if you gave every waking hour, you would still fall short of every demand placed upon you. That tension is not a personal weakness—it is the reality of the profession.

Being a doctor means learning to live within that paradox. Learning to be comfortable being uncomfortable is essential. It requires accepting uncertainty, imperfection, and limits, and recognizing that your own well-being matters. The standard pre- flight message reminds us that in an emergency, oxygen masks drop from the ceiling—and you must secure your own mask before helping others. The same is true in medicine. Without taking care of yourself, you cannot provide the best care for those who depend on you.

Another critical lesson to learn early is that being a doctor is what you do, not who you are. Your profession cannot be allowed to define your entire identity. You must make room for the other roles and relationships that shape you as a person. You are also a son or daughter, a spouse or partner, a friend, a parent, a person of faith, and a member of a community. Neglecting those parts of yourself does not make you a better physician—it eventually makes the work unsustainable.

This work is hard, but it matters—and you are not alone in it. Seek out mentors who will speak honestly, encourage you, and help you see beyond the next hurdle. Develop healthy habits early. Don’t fall into the illusion that balance will come later—after residency, after fellowship, or after the next promotion. There will always be another milestone to chase. If you postpone caring for yourself until “later,” later rarely comes.

Finally, I would encourage you to see medicine not as something to be conquered, but as a journey—one to be navigated with curiosity, humility, and gratitude. When medicine is kept in its proper place, it can be deeply fulfilling rather than consuming. You don’t need to have it all figured out right now. You simply need to keep moving forward with intention, perspective, and grace—for your patients, and for yourself.

Connect with DR. Kang: Lean more about his work and mission: