- April 1, 2024

Kyoung Ryul Lee, MD, PhD, CEO of the SCL Group, Seoul Clinical Laboratory, a Specialist in Laboratory Medicine

Kyoung Ryul Lee, MD, PhD, CEO of the SCL Group, Seoul Clinical Laboratory, a Specialist in Laboratory Medicine What motivated your decision to attend medical school and become a physician? Could you share some particularly

- August 5, 2024

ISSUE 28

FROM THE PUBLISHER W elcome to the 28th edition of the World Asian Medical Journal. This issue encompasses a captivating cover story featuring an interview with Dr. Huang, a distinguished medical professional whose journey from

- August 5, 2024

Youngmee Jee, MD, PhD | Inspirational Asian Healthcare Leader

INSPIRATIONAL ASIAN HEALTHCARE LEADER Youngmee Jee, MD, PhD Commissioner of Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency INTERVIEW 01 Tell us how you decided to pursue a career in medicine. How did you choose your specialty?

- September 21, 2024

Rethinking Hypothyroidism

Rethinking Hypothyroidism: Why Treatment Must Change and What Patients Can Do Author: Antonio C. Bianco, MD Translated by: Semin Kim, MD & Sihoon Lee, MD About the book “Rethinking Hypothyroidism” The limitations of current

- October 1, 2024

The Internet of Things (Revision 2021)

Purchase LinkThe Internet of Things (Revision 2021) Author: Sam Greengard We turn on the lights in our house from a desk in an office miles away. Our refrigerator alerts us to buy milk on the

- October 1, 2024

Superconvergence

Purchase LinkSuperconvergence Author: Jamie Metzl In Superconvergence, leading futurist and OneShared World founder Jamie Metzl explores how artificial intelligence, genome sequencing, gene editing, and other revolutionary technologies are transforming our lives, world, and future. These

- October 12, 2024

The Strategic Importance of Location in the U.S. for Foreign Bio and Pharma Companies

The Strategic Importance of Location in the U.S. for Foreign Bio and Pharma Companies DoHyun Cho, PhD (CEO, W Medical Strategy Group) The U.S. Market: A Cornerstone of Global Expansion For pharmaceutical and biotech companies,

- October 12, 2024

South Korea’s Healthcare Crisis: Beyond the Numbers

South Korea’s Healthcare Crisis: Beyond the Numbers Dongju Shin, Dong-Jin Shin INTRODUCTION The South Korean healthcare system has recently plunged into a significant crisis following a February 2024 announcement by the government to increase medical

- October 14, 2024

Overcoming Disparities in Gastric Cancer Care

Overcoming Disparities in Gastric Cancer Care Chul S. Hyun, MD, PhD, MPH Gastric Cancer and Prevention Screening Program, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide,

- October 15, 2024

The Global OR – An Introduction to Global Surgery

The Global OR – An Introduction to Global Surgery Kee B. Park, MD, MPH, Dawn Poh, MBBS, MRes Introduction An estimated 5 billion people worldwide lack access to timely, affordable, and safe surgical care, including

- May 1, 2025

- COVER STORY

Interview

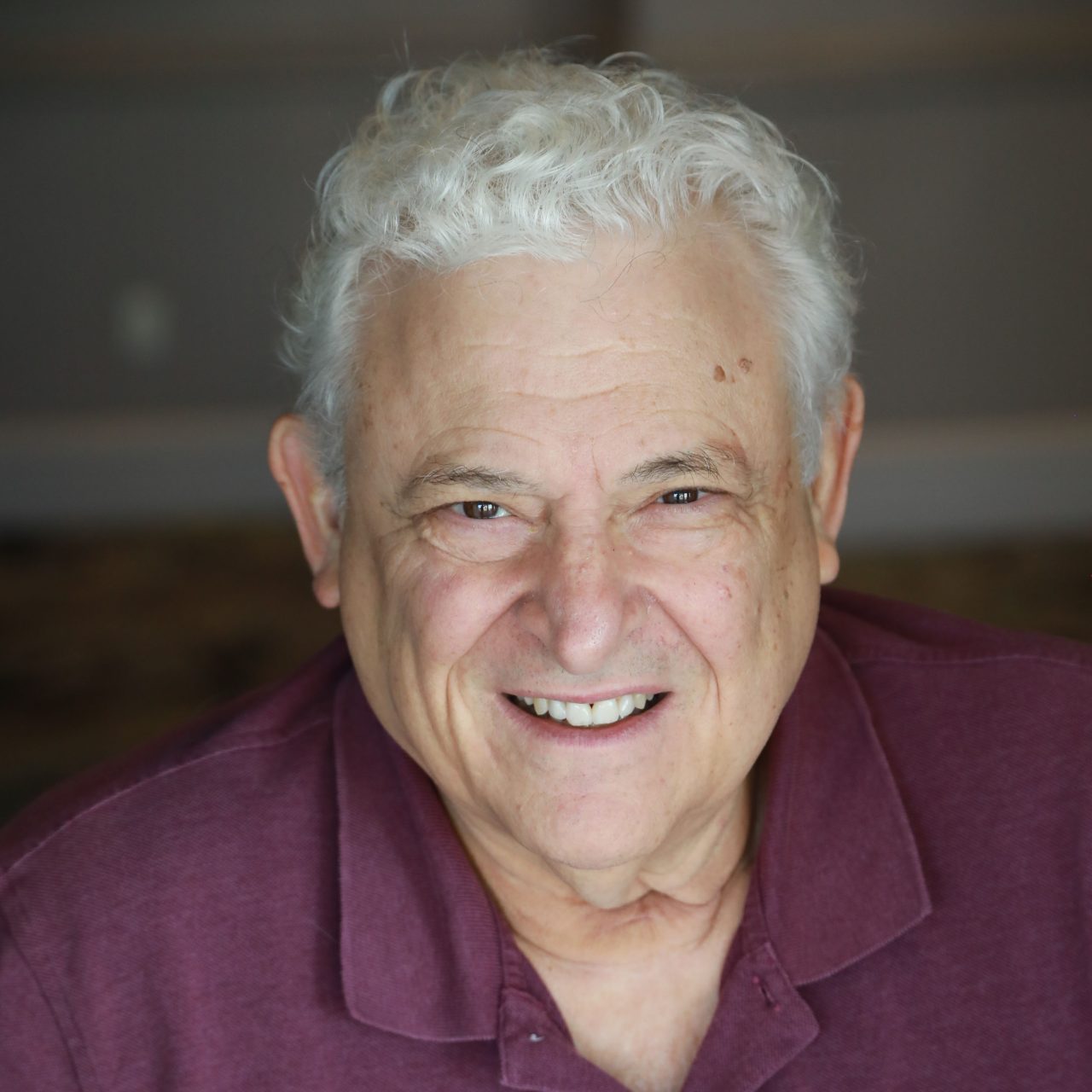

A Pioneering Voice in Bioethics: Arthur Caplan, PhD

In this timely and thought-provoking interview, NexBioHealth Editor-in-Chief Dr. Joe McMenamin speaks with Dr. Arthur Caplan, a pioneering figure in bioethics and founding head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Together, they explore pressing ethical challenges in medicine today—from the growing influence of insurers on clinical decisions to vaccine hesitancy, end-of-life care, and the rising role of AI. With honesty, clarity, and wit, Dr. Caplan offers invaluable insights for young physicians and students navigating the changing landscape of modern healthcare.

Dr. McMenamin: How are you? I’m good. Thank you. How are you? Good. I appreciate you taking the time.

Dr. Caplan: No problem. Happy to do it.

Dr. McMenamin: This is an interview with Dr. Art Kaplan, a well-known bioethicist in New York. And we have several questions we’d like to pose; the first, about conflicts of interest: To an unprecedented extent, American doctors today are employees and not in independent practice.

They owe duties, then, both to patients and to their employers. How should they weigh those obligations? And where inconsistent, determine how to proceed? For example, suppose on the basis of a thorough workup and the best available evidence, a physician is convinced that a given patient requires expensive treatment urgently.

Yet in the doctor’s healthcare system, a stepped care approach is mandated, under which a time-consuming series of failed approaches must be taken first. What should the physician do?

Dr. Caplan: Well, tough situations, and they arise, sadly frequently in our health care system because we have not only third-party payers setting, if you will, what they’ll pay for, but increasingly, starting to tell the doctor how to practice.

So: step therapy. Meaning, in many instances, start with something perhaps cheaper at a lower dose, see if that works, and then escalate up to more expensive drugs and, maybe at higher doses This approach is not uncommon in terms of what the insurance company wants. But I have to start by saying having third party payers practice medicine, which is what you’re doing when you’re saying, not only this is the drugs that we cover, but this is how to use them, I think is ethically inadvisable and flat out ethically wrong.

I think that medicine, nursing, pharmacy should be fighting back more vigorously against the intervention of third parties in the practice of medicine. So, the first thing to do about conflicts of interest is to get rid of them. It’s to not have them. And the way you do that, in many instances, is long before the patient is there, you’re negotiating what you will and won’t put up with from a private insurance company.

Or what Medicare says it’s going to do or what the VA says it’s going to do. And again, just to repeat: In the old days, there certainly were limits on both what procedures might be covered and what drugs might be in a so-called formulary. And you couldn’t get something paid for if it wasn’t in your formulary.

But we are escalating and escalating to the point where now people are saying, Well, if you’re going to do a procedure, you have to do it this way. Or if you’re going to do a knee replacement, you’ve got to use this joint with these technicians and this type of anesthesia. And that’s going way beyond setting fiscal limits, in terms of what somebody can afford for their premium to here’s how to practice.

And it’s just a bad, bad, situation to not only permit, but not to aggressively, if you will, fight back against. That said, here we are, and it does exist, and so tomorrow morning some people are going to wake up as doctors or maybe nurse practitioners and find themselves in the situation you described.

“I think you need X, but your payer says we can only do Y, and we have to do Y gradually, so for the next six months. Even though you have horrible migraines, I’m going to try three other drugs before I get to the one that I think is best for you.” I think first patients need to know that this is going on.

So the first way to manage a conflict is to disclose it to the patient. Why? Well, the patient may say, “I’ll pay the difference.” Not all can, but some do. I’ve seen it. They will say, “I don’t want to wait. You get reimbursed what you get reimbursed and then I’ll fill in the difference and let’s go to what you think will work best for me.”

Secondly, the patient may want to protest to the payer and say, “Look, I know you have this step therapy, but that’s a one size fits all situation.” I’m just making this up now. “I have had migraine for 10 years. None of those things has ever worked when I’ve tried them with other doctors. You’re making me go back and do it again.”

“It doesn’t make any sense. I want you to reconsider for me what it is that you’re doing.” The company may be thinking, “Well, I’m not sure we could do that because it might set a precedent,” but that’s their problem. It’s not the patient’s problem. So the patient does have the right to appeal and the doctor can certainly pile onto that, help out with that to the extent time and patients permit.

I certainly talked to a lot of physicians who said, “I don’t want to spend all day, every day talking to third party insurers about their limits and requirements.” The third thing to do when you’re on the edge, you may lean harder into saying, “I think this is necessary.” And, you know, there’s a fine line between a fraudulent diagnosis, just lying to get somebody something, and then saying someone’s right on the gray zone or border. “I think this drug would help your asthma or this inhaler if that was more expensive, but it’s only indicated for someone who has, let’s say, three bouts a day of asthma symptoms, you seem to have 2.”

Well, I’m leaning into three, and I think that’s what good advocacy does. It puts the patient first when possible. I’m not saying make up information. I’m not advocating lying, but look, people bring up that objection all the time. My experience has been, very often, it’s not so clear and you could go either way.

And so I think you should be leaning into what the patient needs in the opinion of the doctor, not what the payer wants in terms of containing cost. The other problem here in managing these types of situations is that I think people sometimes forget. Patients don’t always do what they’re told.

Noncompliance is an issue. You say, “Do this and take it this way,” and they don’t do that or they say, gee, I feel pretty good today. I’m not taking my blood pressure med anymore or whatever it is. By the way, I do that. I’ve been known to stop my antibiotics a little early relative to what I know is a necessary course.

So to maximize the efficiency of whatever is being done, I do think it’s important to remind everybody about this issue of noncompliance. It may be that the cheaper thing would work if they did it the right way. Or took it at the right time or took it to the end of the course. You know, you look at the statistics out there.

I’m going to say something like 50% of people either don’t fill their prescription, or don’t take it the right way. So it may not just be a matter of, “Gee, I think this is best for you, and you’re not getting what I think is best.” Sometimes it’s, “I got to work with you to make sure you’re doing what’s minimally necessary” to see if something would be helpful.

I think we underplay a little bit the magical powers of prescribing to get people to actually do something. It’s: they’re busy. They get distracted and also, they have their own remedies, right? The other thing to look into is if you say, “Well, I’m not sure this is the best place to start, but let’s see how it goes for three months.”

Then they say, “Gee, I’ll go online and I’ll find four other things from corn syrup to milk of magnesium. I’ll try that, too.” So you want to be making sure that whatever they’re doing, you know about it.

Dr. McMenamin: Thank you. Good answer. I’m guessing that if on occasion even you deviate slightly from the prescribed course that that can’t be all that rare in the general population.

Dr. Caplan: Let me tell you. I’m also told occasionally not to eat donuts, but here we are.

Dr. McMenamin: I’d like to turn to a question on public health. And I think it’s particularly timely today, given events in Texas and elsewhere: Many parents have been influenced by anti-vaccination publications and litigation. Among other consequences, this has resulted in outbreaks, even in wealthy industrialized nations, of diseases that have long been preventable, but remain difficult to treat.

What should the clinician do about a child whose parents want to bring him in for care, but who decline to allow the child to be vaccinated? Is it ethically permissible, for example, to allow that child to be in the presence of other children, vaccinated or not, in the waiting room or elsewhere?

Should the physician recommend that the child be homeschooled so that other children are not exposed to an unvaccinated peer?

Dr. Caplan: Well, sadly, as you noted, the problem of not vaccinating is getting worse. And during our conversation today, we’re watching a dangerous measles outbreak begin to spread both in West Texas, but also popping up elsewhere.

There are three cases in New Jersey as we’re speaking today and other cases. partly due to travel. Those cases seem to have come from other countries into us. Measles, for example, is certainly a problem in many countries. And with airplanes and boats, and even cars and trucks, things can get from one place to another pretty quickly and do.

So under-vaccination of the population and vaccine refusal is something that is getting worse. I think it got worse because people were very disappointed in their ability to do something about COVID. Initially, I think everybody thought when COVID first appeared and was in its most lethal form that public health and American medicine and science would knock it down pretty quickly. And that didn’t happen. And we suffered something like a million deaths or more in the country. And by the way, especially ravaged were older people. People in nursing homes had tremendous numbers of deaths.

My mom died in a nursing home in Massachusetts at 95 from COVID and 95 seems like a good life and it is, but she was, you know, hearty and cognitively there, she was somewhat frail, but certainly was enjoying her life. So it wasn’t a death that one would accept as a conclusion of a life. It was still premature, even for her.

What happened in the COVID outbreak was then we moved to traditional public health measures: quarantining, isolating, masking, mandating. And the American people, I think, got very angry, and panicked that they were going to lose their liberties, that they were going to wind up unable to go where they wanted and mingle with whom they wanted.

And their kids would be out of school. And it just set off a backlash that I think we still live with today. And that’s where I think the anti-vaccine movement or phenomenon arose. It’s really both fear of plagues, and disappointment that you didn’t get a quick fix. I think people thought, “Well, you know, we’re transplanting faces and transplanting pig kidneys. What’s this little viral outbreak going to do? We’ll get that under control in a couple of months.” And it didn’t happen. And then we had this legacy of the old-fashioned public health interventions. As I say, isolate, shut down mobility, mask. Mandate masks, real restrictions on lifestyle and on choice. And that just didn’t sit well with people leaving us with a hostility toward vaccines, somewhat toward public health.

So to get to the specific question, what do we do now when a parent says, I don’t want to vaccinate my kid or doesn’t vaccinate their kid? You pointed out one thing. Some people say, well, let’s keep the kid more isolated, go to homeschooling. And by the way, there’s only one state that had on its books vaccine requirements for homeschooling. It’s a good bioethics trivia question, but it was North Carolina. I don’t know if they still do, but they did. And if you said, why them? I have no idea. But they did. Everybody else, if you stay in homeschool, you didn’t have to vaccinate. Nobody came to your door and said, “You know, can you show me a vaccine certificate for whoever’s homeschooling here?” Or a semi private academy kind of thing, where they might have more than one kid?

I don’t think homeschooling is the answer for a simple reason. People who homeschool don’t just lock their kids up at home. They still go to airports, bus terminals. They might play sports. Many of the kids who homeschool go to the public school for athletics or band or theater. So I don’t think they’re as isolated as one might think. When you hear the term homeschool, I don’t think that’s going to protect against a highly contagious disease like measles, for example. I think they could get it, or they could bring it, depending on which way the transmission is going. So, I think we should encourage homeschooling, to understand what I just said, and say that it’s still very important as the measles epidemic spreads.

I think more parents are going to rethink their opposition. You got one in 15 kids going to the hospital. I know RFK, Jr. and Donald Trump have said, “There are kids in the hospital because we’re quarantining them.” Nobody quarantines a kid in a hospital. They’re there for respiratory problems and treatment.

And parents know that and will see that. And sadly, the impact of not vaccinating for a highly contagious disease like measles is the occasional death and a lot of hospitalization. So, I’m thinking, that’s a message we have to take advantage of right now. “Look, here’s what happens if you don’t do this, whatever your worries about the safety of MMR vaccines.”

And I think they should be minimal. I’m not going to say there’s zero, but they’re tiny relative to the benefits that we can get for your kid and your kid’s friends and the community kids. Let’s rethink what we’re doing here.

So that would be my first approach: to redouble efforts right now to try to get people going with vaccination as a defense against measles. Then you can extend it, obviously, to cervical cancer or whatever other, once you regain some of the trust, which has been lost. Pediatricians, I think, face a special issue, and you mentioned it. Who’s getting into my office? Who do I want in the waiting room? I know a couple of pediatricians who say, “If you won’t vaccinate, I’m not your doctor.”

And there are days when I wake up and say, that’s right. Be tough. See if they knuckle under and get vaccinated. But for some families who won’t vaccinate, you could be the only pediatrician for a lot of miles, and that leaves the kid with no care. So I don’t think that’s a good approach. What I do think is a better approach is to say, “If you won’t vaccinate, you’re going to have to come at four o’clock or later. That’s when the unvaccinated kids are all here, and we’re not going to expose you to the other patients. We’re going to control access to try and minimize risk to everybody else. And while you all are sitting around in the waiting room, I look at your kid. I’m going to put out videos and written materials about why vaccination is important. Testimonials from parents who said my kid got meningitis or my kid got whatever and this was really horrible.” We need some education and we got to work on this together. So I wouldn’t cut them off. I used to sometimes think that was hard love, you know, do this or else. But I worry that too many people just say, “Well, then I won’t go, and shifted over more toward particular hours with particular education efforts that are aimed at them.

One other thing I think it’s important to point out that the doctor got vaccinated. The doctor’s kids got vaccinated. I think people are more impressed. Not just about what ethicists say is important about helping the community or doing the right thing. I think they watch their doctor and they say, “If you did it and your kids did it, and you know, you recommend everybody in the family do it” and you follow through.

I think that shapes behavior quite a bit. I would not underestimate the power of a good doc as a role model. Let me divert a little on that. Sometimes people say, “Well, my doctor’s overweight. So why should I pay attention?” Well, even there, I think you could say something like, “Look I have a weight issue. I struggle with it. I’m going to work with you on it. We can work on it together.” It’s not like an overweight physician or nurse is unaware. And they certainly are aware that they’re talking about. Health and weight with their patients. But even there, I think identifying a common struggle could be good.

That’s why I made that little wisecrack about donuts earlier. It’s like, I know I’m not supposed to eat them. I try not to eat them very much. So if I can agree, sometimes I’ll just eat a quarter of a donut. Sometimes I’ll have a splurgy day, but on the whole, they’re bad for you. And I think we should watch what we eat.

I’m in favor of that. So finding ways to identify with the patient, work with them on whatever their worries are. It wouldn’t even bother me if a doctor confessed, “You know, I don’t like giving 10 shots to these kids. I know they cry and it’s uncomfortable and I get it. You don’t like it either. I get that you don’t want to hurt your child. There’s nothing ignoble or immoral about that. But as you know, often in health or medicine, I have to take a little pain to get a little reward or bigger reward.” So maybe those are paths.

Dr. McMenamin: Thank you. I have felt guilty myself about the role of the legal profession.

I spent a few years of my life defending pharmas. That were sued on the theory that their vaccines or the preservatives used in the production of those vaccines had caused developmental delays, including some very serious cases, autism and the like. And it has made me very attuned to this issue. So I’m happy to be able to blame COVID and not my fellow lawyers for this problem.

Let me turn to a third question. This one concerning end of life questions, which I have to guess are pretty commonly bandied about in your world.

Classically, passive euthanasia has been distinguished from active euthanasia. Is this distinction still valid today? In those jurisdictions where active euthanasia is lawful, what should a physician conscientiously opposed to the practice do when a patient she is responsible for requests assistance in dying?

What criteria of competency are sufficiently rigorous?

To justify the conclusion that the patient seeking euthanasia is competent and acting in a manner consistent with her own autonomy, AI is being developed to assist in, among many other things, end of life care, such as predicting life expectancy or guiding treatment options.

What ethical challenges should healthcare providers be mindful of when integrating AI into such sensitive areas?

Dr. Caplan: Well, first, let’s get AI out of the way. AI is not yet ready to act as a counselor to a patient about matters involving end of life care. It’s not sophisticated enough. A lot of the AI chatbots simply surf the Internet, pulling information from random sources, not vetted, not curated in any way.

So they’re just picking up whatever is lying around out there on the Internet and it’s not trustworthy. And then key matters like health and end of life care. I think what AI is most useful for is to offer people advice on what the law might be in the place where they live or what their rights are in the place where they live, or how to get in contact with, say, lawyers who specialize in managing end of life planning and retirement and medical power of attorney decision making. It’s good as a traffic cop to help people get around a complicated geography, but it isn’t a substitute. Absolutely not. I would never trust it right now. Someday we’ll see, but that day isn’t here yet. I’ve seen too many false, crazy, bad bits of advice. AI has not learned to be empathetic.

AI stinks at reading human emotions. It just doesn’t do it. It’s not very good at spiritual help or religious type counseling. So it’s a tool, but I would say, in end of life care today, it’s a limited tool. I wouldn’t rely on it as a substitute.

Is there a difference between active and passive in terms of what gets done when people are dying? Absolutely a difference. For example, on the passive side, there are many people who are very sick and are dying where we have long agreed we’re not going to start new things to keep them going longer. And we could. I spend a lot of time in ICUs, spend a lot of time around critically ill people, and spend a lot of time around dying people.

There’s always something you could do to extend their life another minute, another 10 seconds, another day. But they may be in pain and it’s life that isn’t going anywhere because it’s not going to cure them, it’s just going to keep them going a little bit more. So at some point, as we all know from television, if you have a crash cart and resuscitation, you’re going to say, “We’re not going to do that again.”

Almost anybody could have resuscitation tried on them at any point, but doctors know they are buying another hour of heart function. That is not meaningful in terms of the person being awake or communicating or experience anything or anything. So they do what’s called the code. We’re done. By the way, it’s interesting.

If you’re 12 and you have a problem that might respond to resuscitation, you’re probably going to see that done six or seven times. If you’re 98 with four fatal diseases and in heart failure, you’re going to see it done once, and I don’t disagree. It’s just the younger person has a better chance sometimes to respond to things.

The older person is very, very sick and frail. Not only won’t they respond, if you start to do chest compression, all that stuff, you’re going to break the ribs and make a disaster. So keep in mind on the passive side, there’s always, always a decision not to do something. We could say, “Hey, you know, Art’s dying and let’s get him a baboon and transplant that heart into him and see if it would work to save his heart that is completely shot.”

We’re not doing that. I mean, we’re not gonna, we’re not gonna spend those resources, we’re not gonna offer it as an option. It’s too experimental, we don’t know what the hell would happen anyway. It’s not done. I could say, “Hey, don’t die here. Let’s get an air ambulance, take it to the Mayo Clinic and see if they could keep you alive for another day.”

Doesn’t happen. People just say, “Your mom, this is it. We’re not going to do anymore.” The point of our interventions is to try and heal people and then to try to make sure they’re comfortable. What’s left that we might try to do doesn’t do either. So we’re not. We’re not going to do anymore. Sometimes the family says, “Well, you must do everything.”

Well, even the doctor needs to know that everything doesn’t mean literally everything. For example, I might say, “Take all the doctors and nurses and just take care of my mom.” I ain’t doing that. That’s never going to happen. My help might get better, intense care, keep somebody going another couple hours?

Not doing that. So doctors have the right, I believe, to say, “We’ve reached the end of what we can do relative to the goals of health care, which are cure or keep comfortable and maintain someone without pain, without suffering.” When you’ve reached the limit of your skills, and there are limits, then I think passive is not the same as saying, “I’m not going to take a pill or an injection and kill you.”

There you’re taking active steps and the death will occur as a direct result of what you’re doing. And as lawyers know, that’s a very different set of actions from saying, “I’m not gonna give you any more blood pressure medicine because I think your blood pressure is just out of control. And if I try this medicine, I’m not going to do much anyway.”

We sometimes invoke what we call futility. Nobody’s going to jail for the decision that they’ve reached the limit of their skills. Even if the patient subsequently dies, you might be going to jail if you walked up to a patient and injected them and they died.

Now we have some states that permit assistance in dying. There were about 10 of them, places like Colorado, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii. New Jersey, Vermont, among others, and other states are considering it. And I imagine in the U.S. the list of states that allow physician-assisted dying will grow. So it’s here, but it is very narrow. Remember, active steps to help somebody die require that you be terminally ill.

So two doctors have to diagnose that you’re going to die inevitably. That somewhat makes the act of providing assistance less like murder and more like facilitating a better death, in the eyes of some. I mean, we could argue, and we do in ethics class, as to whether there’s much difference there. But for many, if you’re going to inevitably die, and someone says, “Well, I can help you die in a way that maintains your dignity or that causes less suffering.”

That’s not quite the same as saying, “I want to just kill you because I don’t think your life is worth living anymore.” That would be unconsented murder. In addition to that, you have to be competent. So people have Alzheimer’s and dementia from strokes. They can’t use this. You have to request it. It is an act in response to a request by a competent individual.

So it’s not the same as someone coming up to the bed and saying, “Boy, you know, Art, it’s pretty expensive, and I don’t think we should be throwing resources into that. Waste of time. Let’s kill him.” I didn’t ask for it. I’m not dying. There’s still a difference between, if you will, murdering me, or homicide, and in these states that allow it, assisting in the dying.

Remember too, in assisted dying states in the U. S., you have to take the medicine. The doctor doesn’t do it. The doctor gets you the prescription, puts the pills by the bedside, after a waiting period to make sure you really want the pills. But you have to take them. So it is closer to assisting in a suicide, if you want to describe it that way, than it is active killing.

So I think these distinctions morally matter. It’s interesting that in the states that have this form of assisted dying, there don’t appear to be abuses. I mean, the states study them and monitor them. And we haven’t seen people with disabilities or people who are poor, disproportionately put into these situations.

So I think it’s worked. Oregon and Washington have had this on their books for 20 years. I’ll end this by saying, I’ve always been surprised. Relatively few people choose to do this because most people want to live as long as they can, so the numbers aren’t big They’re small, and of the people who get the pills in states like Oregon and Washington, maybe two-thirds of them wind up using them. But a third don’t and if you ask the third who don’t, “Why didn’t they ask for them?” They say well, “It’s like having a parachute. If things got really bad I would take it and I liked knowing it was there, but I didn’t use it. And I told my family I’ll die without taking the pills because I can bear this. That’s what the families report. So in a weird way, having the law in the books may prevent some people from suicide.

They might have used a gun or OD’d on pills or whatever, because they felt they were given an option, but then they choose not to use it as much. So in the U.S., not abused. One warning: In Holland, in Belgium, and in Canada, you’re starting to see people say, “We want the right to end our lives, not because of terminal illness, but because of pain and suffering.”

I don’t go along with that shift in moral standard because it’s too broad. You could say things like, “I want to end my life because I had a divorce and I’m suffering. I want to end my life because I lost my job and I’m suffering.” It makes the eligibility for help in dying way too broad. People get depressed or upset.

They can qualify. I think those countries are going down the wrong road.

Dr. McMenamin: Well, thank you. Now this has been fascinating. I’m, I am conscious of the value of your time and we have consumed the 30 minutes we agreed to.

Dr. Caplan: And then you can let me run.

Dr. McMenamin: Well, I’ll leave it at that.

Dr. Caplan: It’s my fault. I’m talking too long.

Dr. McMenamin: You’ve done a beautiful job and I appreciate it. But should we turn to this fourth or shall we call it a day?

Dr. Caplan: We can do one more. I’ve got five more minutes. I’ll just, I’ll, censor myself.

Dr. McMenamin: This has to do with consent to artificial intelligence and its use. What information should the physician impart to the patient respecting the use of AI in her care? Does the doctor have a duty to ascertain, and then disclose, the degree of similarity between the sources of training data and the patient’s demographic group? If so, how are such groups to be defined?

Has the doctor a duty to reveal how much experience he himself has with the use of AI in health care generally and or in circumstances such as this specific patient’s? Does he have a duty to adduce data on the costs and benefits of AI-augmented care versus conventional care for the patient’s diagnosis? What if such data do not yet exist or are of doubtful validity?

What if the AI comes up with a recommendation the physician disagrees with? Does he still have an obligation to reveal that recommendation?

Dr. Caplan: Well, part of the way to answer that question is to say those are going to be the questions that require answers in the next five years.

We don’t have enough AI practice out there yet. To even get close to saying, “Well, what’s right for Joe is not right for Art,” or personalize it. Right now it’s a pretty broad brush use of medical information, usually built on categories of disease and disease type. I think, also, there is a lot of AI in use already in healthcare, but it’s not in the doctor-patient relationship.

It’s humming in the background where your medical records are kept. You may see certain tests. In radiology or lab medicine, or your pap smear sent out, looked at by an AI scanner and then returned. Do you need to know that as a patient? I doubt most people would care. In fact, it’s probably doing a better job than human eyeballs and people who get tired and had a bad night of sleep before.

The machine doesn’t get tired and it sees, oftentimes, more accurately than the human eyeball. Do we need standards, by the way, to govern that? Yes. They’re slow in coming for AI reading of diagnostic information, but it doesn’t keep me awake at night worrying that somehow I’m going to be mistreated because this thing was read by a machine.

In fact, it makes me feel a little better, knowing some of the situations my colleagues are in occasionally trying to read these things. So, I mean, emotional state or tired or hungover or whatever they are. So, there, I think there’s not much room to worry yet. But we do need to understand AI is out there in the background.

Our records move around the NYU health care system from doctor to specialist. From specialist to nursing home, from one of our hospitals to another hospital. That’s all AI now. It’s not paper. There are no more charts. We don’t run down the basement and say, “Give me a file,” you know, and come out with a four pound thing of bad penmanship.

It’s moving along and it’s bad having all that, but there are certainly situations in which somebody might say you missed the diagnosis. And if you’d used AI, it would have reminded you that these rare symptoms could have been something which you didn’t remember or you forgot. So that’s augmented patient care right now.

I think doctors do have an obligation to be up to the standard of care. So, as the law will often point out, what’s customary, what is approved by medical groups in a particular region, as to be expected, will say what the action should be in the doctor. If a lot of doctors in a specialty are using AI to remind them about diagnostic possibilities or therapeutic options, then you better be doing that too, and it’s perfectly fine to say to the patient, “I think A and B are possible, but I have checked with our AI database and there’s two other things that are popping up here and I wanna test for them.” I think that’s gonna become the standard of care. And if you’re not doing it, you’re gonna get in trouble and you should, because you’re not following the best practice in terms of, you know, supplementing your fallible memory with things that the machine can at least bring to your attention, both diagnostic and therapeutic.

The other issue that comes up, in terms of where AI is being used right now, is when you get AI care online. So there are companies that are saying, “Do psychotherapy online.” There are companies out there–I’ve seen them–that say, “Do you have a mole that’s worrying you? Well, go online, show it to us on video or send us pictures and we’ll diagnose it.”

That I think is trouble. There are no standards yet for what’s expected, who should be doing this. What conflicts of interest they have if they’re prescribing medicines or actions in response. That area I think is under regulated and I think may not be up to snuff in terms of quality of care yet.

So I like the use of AI to supplement human memory. I like the use of AI to replace human labor when that labor could get tired. We’re exhausted or maybe not even be as perceptive as machines can be in reading certain things, but for the most part, we better start thinking harder about standards of care, malpractice.

Whose jurisdiction is involved when somebody uses telemedicine? What the need is to disclose the presence of AI and when? I don’t think most patients care what’s going on with information exchange in the background. But I think they’ll be very interested in knowing, you know, if AI is doing the recommendation of what it is that’s the best treatment for me.

So we got to really work on that over the years to come. Otherwise, it’s going to turn into a sort of Wild West where it’s going to be buyer beware.

Dr. McMenamin: Very good. Thank you very much. You’ve been generous with your time. As we discussed, we’ll develop a transcript of this and provide it to you.

Again, thanks very much. Really appreciate it. Good of you to take your time. Very good.

Dr. Caplan: Glad we got it done. It was a great time. Thank you. Take care now. Thank you. Bye now.

Arthur Caplan, PhD

Dr. Arthur L. Caplan is a prominent American bioethicist, currently serving as the Drs. William F. and Virginia Connolly Mitty Professor and founding head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. He earned his PhD from Columbia University and has held academic positions at the University of Minnesota, where he founded the Center for Biomedical Ethics, as well as at the University of Pittsburgh and Columbia University. Dr. Caplan has authored or edited over 35 books and more than 870 papers in peer-reviewed journals, contributing significantly to the fields of bioethics and health policy. His work has been instrumental in shaping public policy, including helping to establish the National Marrow Donor Program and creating the U.S. system for organ distribution.