By Ashlesha Chaudhary, Carlos Espiche Salazar, Andrew Krumerman and Daniel Katz.

- April 1, 2024

Kyoung Ryul Lee, MD, PhD, CEO of the SCL Group, Seoul Clinical Laboratory, a Specialist in Laboratory Medicine

Kyoung Ryul Lee, MD, PhD, CEO of the SCL Group, Seoul Clinical Laboratory, a Specialist in Laboratory Medicine What motivated your decision to attend medical school and become a physician? Could you share some particularly

- August 5, 2024

ISSUE 28

FROM THE PUBLISHER W elcome to the 28th edition of the World Asian Medical Journal. This issue encompasses a captivating cover story featuring an interview with Dr. Huang, a distinguished medical professional whose journey from

- August 5, 2024

Youngmee Jee, MD, PhD | Inspirational Asian Healthcare Leader

INSPIRATIONAL ASIAN HEALTHCARE LEADER Youngmee Jee, MD, PhD Commissioner of Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency INTERVIEW 01 Tell us how you decided to pursue a career in medicine. How did you choose your specialty?

- September 21, 2024

Rethinking Hypothyroidism

Rethinking Hypothyroidism: Why Treatment Must Change and What Patients Can Do Author: Antonio C. Bianco, MD Translated by: Semin Kim, MD & Sihoon Lee, MD About the book “Rethinking Hypothyroidism” The limitations of current

- October 1, 2024

The Internet of Things (Revision 2021)

Purchase LinkThe Internet of Things (Revision 2021) Author: Sam Greengard We turn on the lights in our house from a desk in an office miles away. Our refrigerator alerts us to buy milk on the

- October 1, 2024

Superconvergence

Purchase LinkSuperconvergence Author: Jamie Metzl In Superconvergence, leading futurist and OneShared World founder Jamie Metzl explores how artificial intelligence, genome sequencing, gene editing, and other revolutionary technologies are transforming our lives, world, and future. These

- October 12, 2024

The Strategic Importance of Location in the U.S. for Foreign Bio and Pharma Companies

The Strategic Importance of Location in the U.S. for Foreign Bio and Pharma Companies DoHyun Cho, PhD (CEO, W Medical Strategy Group) The U.S. Market: A Cornerstone of Global Expansion For pharmaceutical and biotech companies,

- October 12, 2024

South Korea’s Healthcare Crisis: Beyond the Numbers

South Korea’s Healthcare Crisis: Beyond the Numbers Dongju Shin, Dong-Jin Shin INTRODUCTION The South Korean healthcare system has recently plunged into a significant crisis following a February 2024 announcement by the government to increase medical

- October 14, 2024

Overcoming Disparities in Gastric Cancer Care

Overcoming Disparities in Gastric Cancer Care Chul S. Hyun, MD, PhD, MPH Gastric Cancer and Prevention Screening Program, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide,

- October 15, 2024

The Global OR – An Introduction to Global Surgery

The Global OR – An Introduction to Global Surgery Kee B. Park, MD, MPH, Dawn Poh, MBBS, MRes Introduction An estimated 5 billion people worldwide lack access to timely, affordable, and safe surgical care, including

- February 1, 2026

- Medical Education

Transforming Medical Education with Artificial Intelligence: An Integrated Perspective

ABSTRACT

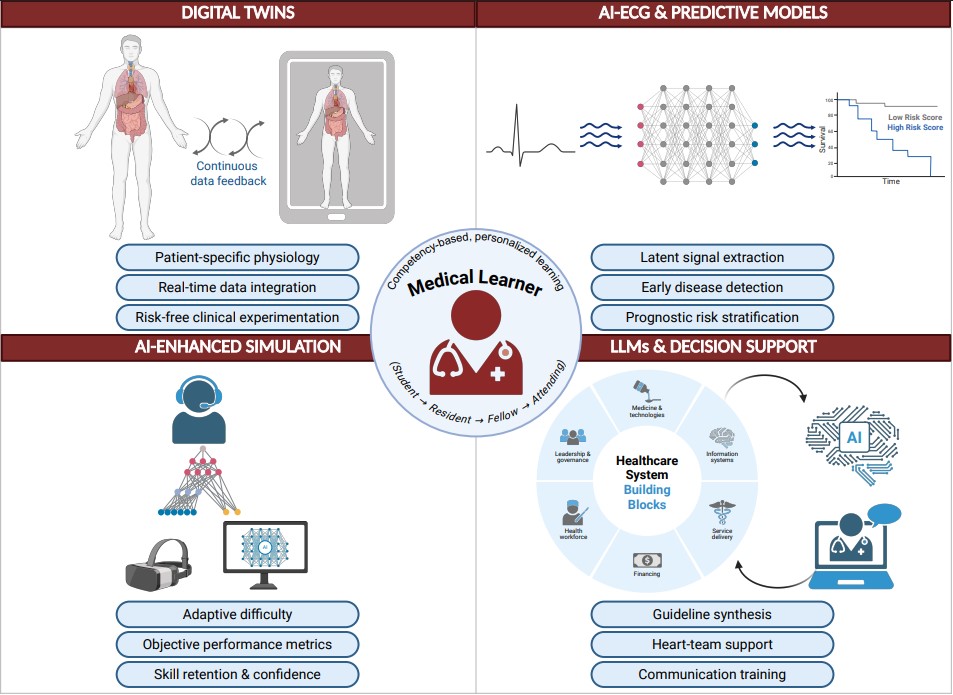

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly reshaping medical education by transforming how knowledge is generated, skills are acquired, and clinical competence is assessed. As AI becomes embedded in routine clinical practice, traditional apprenticeship-based training models are increasingly strained by rising patient complexity, expanding medical knowledge, and heightened safety expectations. This review provides an integrated perspective on the educational impact of contemporary AI technologies, including digital twins, deep learning–enabled electrocardiography, AI- enhanced simulation, and large language model–based clinical decision support. These tools enable personalized, competency-based learning at scale, offering high-fidelity, data-driven environments for risk-free experiential training, prognostic reasoning, and procedural skill development.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Figure 1 illustrates an integrated framework of AI tools supporting medical education across learning domains.[1]

INTRODUCTION

Medical education is undergoing rapid transformation as artificial intelligence (AI) becomes embedded in clinical practice.[2] Promotion and assessment of knowledge, clinical skills and competence are domains for which AI may enhance medical education. AI can promote personalized learning plans tailored to an individual’s needs. Traditional training models, largely dependent on apprenticeship and variable clinical exposure, are increasingly strained by rising patient complexity, expanding medical knowledge, and heightened safety expectations.[3] [4] As AI-driven tools reshape diagnosis, risk prediction, simulation, and clinical decision-making, medical education must evolve to prepare physicians to use these technologies critically and responsibly.

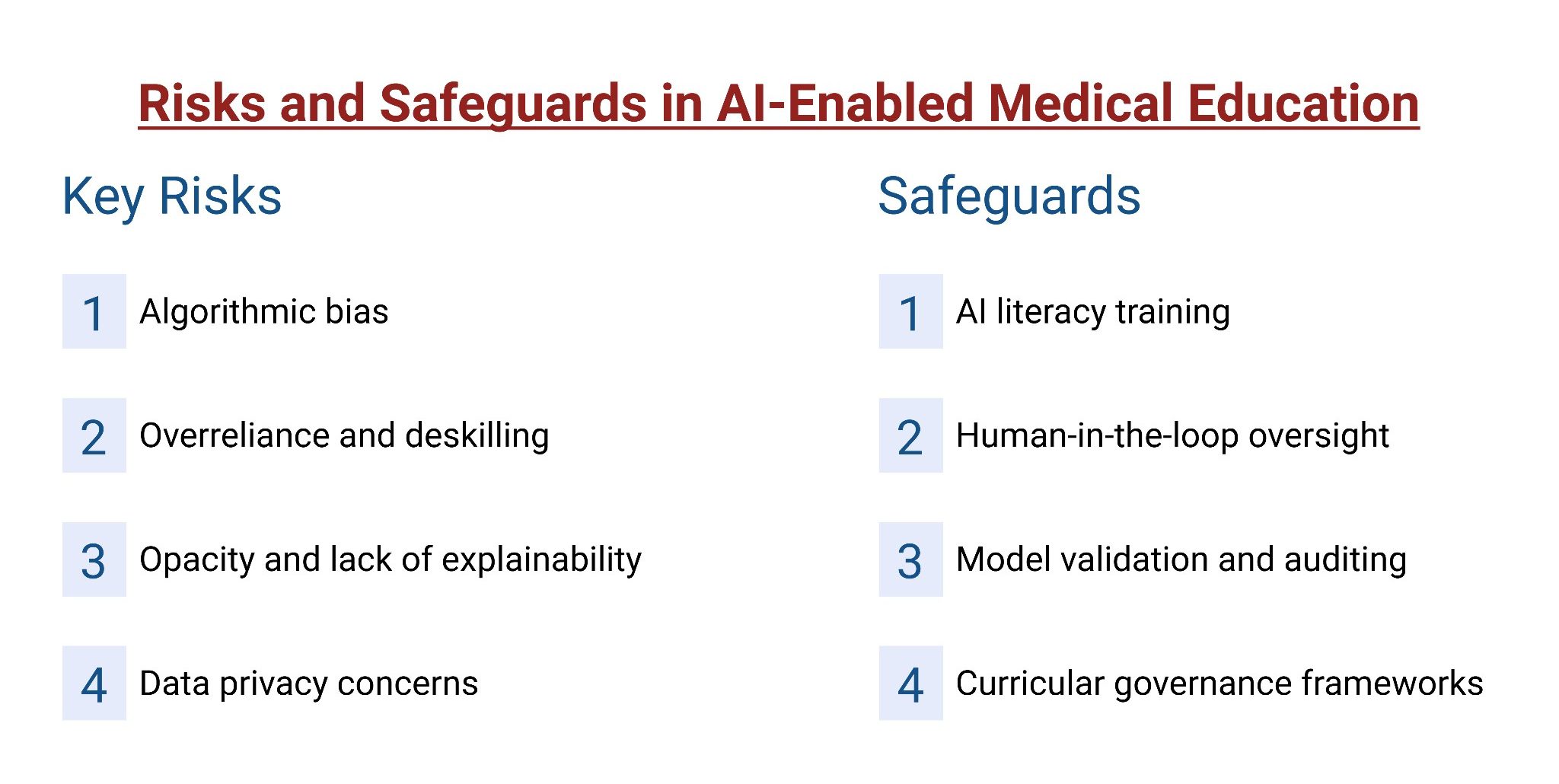

Unlike earlier digital innovations, contemporary AI alters how clinical knowledge is generated and applied. Deep neural networks can extract prognostic signals from routine tests, digital twins can model patient-specific physiology, and AI- enhanced simulations can recreate complex or rare clinical scenarios with adaptive realism.[5] [6] [7] Extended reality may simulate procedural experience to promote competency and improve safety. These advances blur the boundaries between education, simulation, and care, enabling personalized and competency-based learning at scale. At the same time, AI introduces new challenges, including algorithmic opacity, bias, and the risk of overreliance or deskilling.[8] This review provides an integrated perspective on how AI is transforming medical education.

1. DIGITAL TWINS IN MEDICINE AND MEDICAL EDUCATION

1.1 Definition and Core Components of Digital Twins

Digital twins are high-fidelity virtual models that replicate real-world systems.[9] Unlike static simulations, digital twins maintain a dynamic, bidirectional relationship with the physical system they represent, allowing the model to evolve alongside changes in patient physiology or clinical status.[10] [11] For example, engineers and clinicians at Duke University have created vascular digital twins that allow surgeons to simulate procedures in a virtual environment before operating on the actual patient, optimizing surgical plans and potentially reducing complications.[11] In essence, from an educational standpoint, digital twins offer a novel paradigm for experiential learning. By creating patient-specific, data-driven representations of anatomy and physiology, learners can explore “what-if” scenarios, test interventions, and observe downstream consequences in a risk-free environment.

1.2 Applications in Medical Training

Originally developed in engineering, digital twins are increasingly being explored in medical education as tools for immersive and personalized learning.[7] [12] [13] Current applications primarily involve medical imaging education, critical care training, and accessibility-focused learning. In imaging, digital twins generate interactive 3D anatomical models from MRI or CT data, allowing learners to explore patient-specific anatomy. In clinical training, they simulate complex ICU scenarios and rare conditions with repeatable practice opportunities.

A notable example is the work by Rovati et al. (2024), who developed a patient-specific ICU digital twin incorporating seven organ systems driven by real patient data.[14] [15] Delivered via a mobile application, the platform allowed residents and fellows to practice managing sepsis and multi-organ failure, demonstrating high usability and reduced cognitive load during decision-making. Similar digital twin platforms have been piloted for emergency response training, surgical rehearsal, and patient-specific intervention planning.[16] Nonetheless, progress has been rapid in recent years, with growing numbers of pilot programs and institutional deployments.[17] [18] [19] [20]

Table 1 summarizes some applications of digital twins in medical education.

| Citation | Digital twin type | Key Educational Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Mekki YM, 2025[20] | Static –> intelligent DTs | Provides a conceptual roadmap linking DT maturity to surgical education, but lacks direct educational validation |

| Sadée C, 2025[11] | Dynamic patient DT | Establishes a consensus definition of medical DTs that can underpin future educational systems |

| Zhao F, 2025[21] | Imaging-driven patient DTs | Demonstrates technical feasibility of imaging-based DTs with educational relevance inferred rather than tested |

| Rudsari KH, 2025[22] | Patient, organ, system DTs | Synthesizes DT applications with clear educational potential but minimal empirical evaluation |

| Zhang K, 2024[23] | DT maturity roadmap | Defines DT maturity stages that are directly translatable to curriculum design |

| Sel K, 2024[24] | Physiologic DT ecosystem | Clarifies engineering foundations required for future cardiac DT-based education |

| Xie H, 2025[25] | Biophysical cardiac DT | Positions DTs as powerful tools for EP training without educational outcome data |

| Trayanova NA & Prakosa A., 2024[26] | Mechanistic heart DTs | Frames DTs as high-fidelity learning environments for advanced electrophysiology training |

| Rovati L, 2024[13] | Patient-specific rule-based DT | First prospective evidence that patient-specific DTs are usable and acceptable for resident education |

| Peshkova M, 2023[17] | Data-centric proto-DT | Demonstrates foundational infrastructure needed for future DT-enabled pathology education |

| Kumar A, 2024[27] | Asset / process DTs | Shows DTs can improve accessibility, but educational impact remains unvalidated |

| Zackoff MW, 2023[18] | Environment-level DT | Demonstrates large-scale, real-world educational deployment of DTs for clinical onboarding |

| Zackoff MW, 2024[19] | Environment-level DT | Confirms tolerability and acceptability of DT-based VR at institutional scale |

| Toofaninejad E, 2024[6] | Conceptual DT framework | Articulates why DTs matter for medical education and identifies key research gaps |

1.3 Advantages and Challenges

Digital twins offer several potential advantages for education. First, they provide high-fidelity realism, enabling immersive interaction with virtual patients or organs that closely replicate real physiology.[29] [30] This supports risk- free, repetitive practice of procedures and clinical decision- making, addressing limitations of traditional training where exposure to complex or rare cases is restricted.[21] [31] Studies report improved learner engagement, teaching effectiveness, and satisfaction compared with conventional educational methods.[13] [32] [33] Because digital twins can be derived from real patient data, learners are exposed to patient-specific anatomical and pathological variability, better preparing them for real-world clinical diversity.[34] [35] Digital twins also promote active learning by allowing trainees to manipulate variables such as medications or device settings and immediately observe physiologic consequences, strengthening clinical reasoning and systems-based thinking.[34] [36] [37]

Despite the promise, digital twin technology in education is still in its infancy and faces meaningful challenges. Development is resource-intensive, requiring advanced imaging, large datasets, computational infrastructure, and multidisciplinary expertise.[13] [38] Integration into curricula also poses difficulties, as faculty must acquire new technical skills to design scenarios and interpret outputs.[39] Most importantly, evidence of educational effectiveness remains limited, with few large-scale studies demonstrating objective improvements in competency, transfer to clinical performance, or patient outcomes. Model validation, data privacy, and the risk of reinforcing incorrect physiologic assumptions also require careful oversight.[40] [41]

2.DEEP LEARNING AND ECG-BASED RISK PREDICTION

2.1 Background

One of the most educationally disruptive advances in clinical AI has been the application of deep learning to electrocardiography (ECG). Algorithms can now identify subtle patterns in ECG signals that are imperceptible to human interpretation, enabling prediction of future cardiovascular disease rather than detection of only current abnormalities. These developments have significant implications for both medical practice and education, especially in cardiology training.

2.2 Implications for Medical Education

Traditional ECG interpretation focuses on detecting current abnormalities such as arrhythmias or ischemia. In contrast, deep learning models can extract latent features from seemingly normal ECGs that predict future disease. Work from the Mayo Clinic demonstrated that a convolutional neural network could identify the electrocardiographic signature of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation even during normal sinus rhythm.[42] Similar models accurately identified reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (≤35%) from ECGs alone, and individuals with positive AI-ECG findings despite normal baseline echocardiograms had a fourfold higher risk of developing cardiomyopathy.[43]

Table 2. Summary of key studies evaluating AI-enabled ECG applications.

| Citation | Clinical focus | Key Educational Outcometh |

|---|---|---|

| Lee MS, 2025[44] | Acute MI | AI-ECG matched or exceeded physician assessment and HEART/GRACE scores |

| Moon J, 2025[45] | Acute heart failure | ECG-based ML identified acute HF with AUROC ≈ 0.89–0.90 |

| Liu W-T, 2024[46] | Asymptomatic LV dysfunction | AI-ECG screening achieved AUROC up to 0.98 and was cost-saving |

| Adedinsewo DA, 2024[47] | Peripartum cardiomyopathy | AI-assisted ECG/auscultation outperformed usual care |

| Liu W-T, 2025[48] | AF detection | AI-ECG alerts improved AF recognition and anticoagulation |

| Lin CS, 2024[49] | Mortality risk | AI-ECG alerts reduced 90-day mortality |

| Tsai DJ, 2025[50] | Low LVEF detection | Earlier low-EF detection without increased echocardiography |

| Ferreira ALC, 2025[51] | HFrEF screening | Pooled AUC ≈ 0.92 supports AI-ECG integration into training |

| Popat A, 2024[52] | Aortic stenosis | ECG-based AI showed high accuracy (AUC ≈ 0.91) |

| Mayourian J, 2025[53] | LV dysfunction | AI-ECG detected current and future LVSD and predicted mortality |

| Surendra K, 2023[54] | HF screening | ECG-only AI matched risk-factor models |

| Gupta MD, 2025[55] | STEMI risk | ML models outperformed TIMI for mortality prediction |

| Hao Y, 2025[56] | Sleep apnea | HRV-based ML showed good screening accuracy |

| Hill NR, 2020[57] | AF screening | Introduced AI-first EHR-based screening strategy |

| Zaboli A, 2025[58] | ECG + MACE risk | LLM ECG interpretation was inconsistent |

| Günay S, 2024[59] | ECG interpretation | Physicians outperformed LLMs |

| Avidan Y, 2025[60] | AF/flutter | LLMs showed unsafe over- and under-diagnosis |

| Gupta MD, 2020[61] | Stress physiology | AI-ECG captured stress signals; clinical value unproven |

| Shroyer S, 2025[62] | Occlusive MI | AI reduced missed OMIs and false cath lab activations |

AI-ECG applications continue to expand, enabling prediction of arrhythmias, ventricular dysfunction, coronary disease, stroke risk, and other outcomes from a single ECG. A notable advance is the AIRE (Artificial Intelligence Risk Estimation) platform, which combines deep learning with survival analysis to generate individualized long-term risk predictions from a single ECG.[44] Collectively, these developments suggest a future in which AI-enhanced ECG outputs generate comprehensive prognostic insights that clinicians must be trained to interpret. As summarized in Table 2, AI-assisted ECG studies increasingly span diagnosis, risk stratification, screening, and workflow integration.

2.3 Advantages and Challenges

For trainees, AI-ECG tools represent both opportunity and challenge. While they enhance diagnostic and prognostic capability, they require AI literacy and introduce risks of overreliance and deskilling.[64] Early AI models were often “black boxes” that gave a risk score without explanation, which made many clinicians understandably hesitant to rely on them,[65] [66] prompting a shift toward more explainable and actionable outputs. For example, the AIRE model generates patient-specific survival curves and demonstrates biologically plausible correlations with established clinical markers.[44] Medical education must therefore train learners not only to interpret AI-generated risk signals, but to translate them into appropriate clinical actions such as closer surveillance or risk-factor modification.[67] Trainees must also recognize limitations, including false positives, false negatives, and demographic bias, reinforcing the need for critical appraisal and human oversight.

3. AI-ENHANCED SIMULATION AND TRAINING

3.1 Background

Simulation has long been a cornerstone of medical education, from anatomy dissection labs and manikin-based resuscitation drills, to standardized patient encounters. AI is now elevating simulation-based training to new heights, making it more realistic, adaptive, and effective.[68] In this section, we examine how AI-driven technologies on simulation are transforming the way medical procedures and clinical scenarios are taught.

3.2 Implications for Medical Education

AI-enhanced simulation enables immersive and adaptive learning environments that closely mirror clinical practice. Virtual reality creates computer-generated operating rooms, emergency departments, and patient encounters, while AI dynamically adjusts scenario progression and provides personalized feedback. A 2025 Scientific Reports study demonstrated that an AI-enabled VR system with haptics and adaptive coaching improved procedural accuracy, efficiency, skill retention, and learner confidence compared with traditional training.[69] These platforms bridge theory and practice by standardizing competency benchmarks while tailoring difficulty to individual performance, and early evidence supports growing adoption across medical schools and residency programs with benefits across surgical and emergency medicine training.[70] [71] [72] [73] [74] [75] [76] AI can support procedural training ranging from novices to experienced physicians learning new skills in a safe environment.

AI has also transformed physical simulation using task trainers and manikins. In cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training, AI-enabled manikins equipped with motion and pressure sensors provide real-time, objective feedback on compression depth, rate, recoil, and ventilation.[77] [78] Systems such as Resusci Anne QCPR and Brayden CPR manikins alert trainees instantly to errors and reinforce correct technique through auditory and visual cues.[79] [80]79,80 Studies consistently show improved skill acquisition, retention, and CPR quality with AI-driven feedback compared with instructor-only training.[81] [82] [83] By the time learners face a real code blue situation, they are more likely to perform high-quality CPR without needing to consciously recall guidelines, because they have been conditioned to the correct technique by the simulator’s feedback.[84] Moreover, AI makes the training personalized: the system can track a trainee’s performance over a session and identify recurring weaknesses. Mobile applications that connect via Bluetooth to a CPR manikin can gamify the experience and provide detailed post-training analytics.85,86 These advances have demonstrated real-world impact and are increasingly incorporated into life-support curricula by organizations such as the American Heart Association and Red Cross.[82] [87] [88] [89] [90]

AI-enabled simulation also supports complex, dynamic clinical scenarios that adapt to learner decisions, fostering critical thinking, teamwork, and decision-making under pressure and help modify patient responses and clinical trajectories in real time. AI-powered virtual patients further extend training into communication and telehealth skills. For example, Weill Cornell Medicine piloted an AI virtual patient system (“MedSimAI”) that allows students to practice history-taking and delivering bad news, while other telehealth simulations using AI-generated patient responses have improved learner confidence and self-assessed competence.[91] [92] Table 3 summarizes applications of AI in simulation and training.

Table 3: Applications of AI in simulation and training.

| Citation | AI Approach | Key Educational Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Raquepo TM, 2025[92] | Computer vision, NN, AR/VR | Improved objective skill assessment and reduced training time |

| Farooq F, 2025[93] | VR/AR, CADe, ML | Enhanced procedural training and diagnostic accuracy |

| Bhakar R, 2025[94] | VR/AR, analytics | Feasible adoption; limited outcome-level evidence |

| Ng ZX, 2025[95] | DL auto-contouring, CDS | Improved feedback and complex case exposure |

| Pan W, 2025[96] | AI imaging, simulation | Reduced diagnostic variability among trainees |

| Escobar-Castillejos D, 2025[97] | ML, DL, CNNs | Automated assessment and adaptive learning |

| Li Z, 2025[98] | VR + ML | Personalized feedback improved performance |

| Borg A, 2025[99] | LLM-enhanced virtual patients | Greater realism and coaching quality vs traditional platforms |

| Truong H, 2022[100] | VR + AI | Faster competency achievement |

| Fazlollahi AM, 2023[101] | AI-guided feedback | Improved safety metrics; noted unintended effects |

3.3 Advantages and Challenges

Across modalities, AI-enhanced simulation offers personalization, scalability, and enhanced realism with improved accuracy, efficiency, and retention compared with traditional training.[69] [103] [104] [105] AI simulations also promote standardization, ensuring all learners encounter core scenarios regardless of clinical exposure variability.[106] [107] For example, every medical student could manage the exact same virtual pediatric anaphylaxis case or surgical complication, ensuring everyone is tested on key learning objectives.[108] This enables safe rehearsal of rare or high- risk events, reduce ethical concerns associated with patient harm, and allow repeated practice without resource constraints.[109] [110] Ethical advantages are also notable: students can make mistakes in a virtual setting without harming patients, and they can repeat procedures until proficient without worrying about resource constraints.[111] [112] [113] [114] [115]

Challenges include cost, infrastructure requirements, faculty development, and concerns about reduced real- patient exposure.[116] [117] AI is intended to augment, not replace, instructors for clinical mentorship, bedside teaching, and reflective debriefing. Additional concerns include simulation fatigue, reduced real-patient exposure, and technical issues such as VR discomfort or software instability.[118] [119]

4. APPLICATIONS OF AI FOR MEDICAL MANAGEMENT AND EDUCATION

Cardiovascular diseases involve complex interactions among therapeutic strategies, clinical decision-making, and drug treatments. AI, especially AI and ML, is increasingly used to improve risk assessment for acute and chronic conditions, enhancing personalized care.[120] As these tools become part of routine care, medical education must prepare trainees to understand, interpret, and appropriately apply AI-assisted outputs. For example, AI-based ASCVD risk calculators embedded in electronic health records outperform traditional scores in predicting individual cardiovascular risk.[121]

4.1 Diagnostic and Clinical Support

Diagnostic and clinical support by AI involves aiding clinicians in acquiring patient history, analyzing clinical features like face and voice, and integrating laboratory results, biomarkers, and imaging.[120] The use of natural language processing (NLP) and large language models (LLMs) can improve diagnostic recognition, guideline adherence, and patient education. From an educational perspective, these systems introduce new learning goals centered on clinical validation, oversight, and integration of AI recommendations into decision-making.[121] [122]

Cardiac imaging has broadly benefited from advances in AI. AI-derived coronary CT measures, such as the fat attenuation index (FAI), provide prognostic information beyond traditional imaging, including in patients with minimal visible atherosclerosis. Emerging techniques such as radiomics and radiotranscriptomics allow earlier and more detailed characterization of plaque biology. These advances shift imaging education toward integrative interpretation that links anatomy, biology, and clinical risk.[120] [123]

The NLPs use information such as history, results examinations, and management for diagnostic and prognostic purposes to answer complex diagnostic questions or help diagnose complex, clinically defined diseases. Wu et al., in a retrospective cohort study, used NLPs to analyze EHRs, including clinical, demographic, echocardiographic, and outcome data on heart failure, and compared AI-driven Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) diagnoses using the ESC criteria and the simple criteria vs the confirmed HFpEF diagnosis, demonstrating that over 91% of the patients with HF and a LVEF >50% on echocardiogram did not have a formal diagnosis of HFpEF and had worse outcomes.[120] [124] Artificial intelligence-clinical decision support systems (AI-CDSS) could assist clinicians in the HF diagnosis. Choi et al. tested their AI- CDSS algorithm in a prospective pilot study using a database of patients not diagnosed with HF and databases of patients diagnosed with cardiovascular HF and non-HF physicians, having a 98% concordance rate with the HF-specialist and 76% with the non-HF physicians; this could provide an excellent tool for regions or institutions without HF diagnostic tools or specialists.[120] [125]

LLMs are also being explored as tools for clinician training and simulated patient interactions. Evaluation of Google’s Articulate Medical Intelligence Explorer (AMIE) across international case scenarios showed strong performance in structured clinical conversations.[126] However, more research is needed, and barriers must be overcome before this can be translated into real-world patient interactions. Ongoing work on multimodal LLMs, particularly in medical imaging, may further expand their educational role.[127]

4.2 Heart Team Decision-Making

Clinical guidelines advocate multidisciplinary heart team (MDHT) discussions in complex scenarios, such as coronary revascularization. Sudri et al. compared the use of ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4 with the MDHT in clinical decisions, achieving concordance accuracies of 0.82 with ChatGPT-4 and 0.67 with ChatGPT-3.5, respectively.[128] From an educational standpoint, AI may serve as a supplementary tool for case preparation, discussion rehearsal, and reflective learning rather than as a decision-maker. Prompt-based reasoning strategies, such as Tree-of-Thoughts methods, further improve alignment with expert consensus in complex cases like aortic stenosis.[129] AI could help interventional cardiologists plan their interventions, base contrast data on each case, and make decisions in complex cases.

5. USE OF DEEP NEURAL NETWORKS

Deep neural networks (DNNs) are a sophisticated deep learning method that uses multi-layered neural networks to learn from large datasets, much as the human brain does.[130] DNN allows the machine to make accurate predictions and decisions and to help train cardiovascular trainees to approach the decision making capability of seasoned specialists.

5.1 Electrocardiogram (ECG) Analysis using Deep Neural Network

Deep learning networks have been used to analyze ECGs in order to improve accuracy and scalability, with encouraging results. DNN achieves an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.97 compared with a consensus committee of board-certified practicing cardiologists.[131] Furthermore, the use of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to analyze ECGs could identify left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF <35%), achieving an AUC of 0.93, and those who were falsely positive in the AI screening had a hazard ratio of 4.1.43 This growing capability of interpretation based on AI gives room to improve the methods used to teach ECG interpretation and the limitations associated with the standard interpretation. Programs such as Waven Maven could include AI processing or the creation of real-world ECG-challenging cases for learners to facilitate improved performance.[132]

5.2 Medical Cardiac Imaging and Deep Neural Network

CNNs can be used to analyze and generate data from complex structures, facilitating the work of cardiac imaging researchers and advancing scholarship in this area.[132] AI enables innovative approaches to analyzing big data and obtaining information, such as the Agatston score, from ECG-gated CT scans of coronary arteries for preventive studies,[140] or for characterizing post-MI scars in cardiac MRIs.[132] The use of machine learning algorithms, including DNNs, has enabled integration of cardiac imaging with vascular biology by associating radiomic features with other biological features secondary to cytokine-related arterial inflammation, creating an algorithm called C19-RS.[123] From an educational perspective, these tools encourage trainees to move beyond image recognition toward integrated understanding of imaging, pathophysiology, and clinical risk.

Table 4 summarizes applications of deep neural networks in cardiovascular medicine.

| Citation | Data Modality | Key Educational Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Hannun AY, 2019[132] | Ambulatory ECG | DNN achieved cardiologist-level accuracy for rhythm detection |

| van de Leur RR, 2020[133] | 12-lead ECG | DNN accurately classified ECGs into acute and non-acute categories |

| Fiorina L, 2022[134] | Holter ECG | DNN-based Holter analysis was faster and non-inferior to conventional interpretation |

| Gumpfer N, 2020[135] | ECG + clinical data | Deep learning detected myocardial scar with moderate diagnostic accuracy |

| Ríos-Muñoz GR, 2022[136] | Intracardiac electrograms | CNN-based models identified rotational activity linked to AF mechanisms |

| Stephens AF, 2023[137] | ELSO registry data | DNN-based ECMO PAL score outperformed conventional prognostic scores |

| Weimann K & Conrad TOF, 2024[138] | Multi-site ECG databases | Federated DNNs preserved privacy while maintaining diagnostic performance |

6. AI TO PROMOTE A SPECIFIC LEARNER’S KNOWLEDGE

The applications and integration of AI into clinical practice should be reflected in the healthcare personnel curriculum, including that of cardiology fellows and medical students.

6.1 Curriculum Development

The concepts of CNNs within DNNs and as an efficient approach to deep learning need to be integrated into cardiovascular education, with a focus on developing computational simulations.[141] AI should be taught as a tool that complements clinical judgment, not as a replacement for it. However, many current curricula lag behind rapid technological advances.[142] Modern competence-based curricula should include structured integration of AI-related competencies, particularly in cardiology fellowship programs.

Cardiac imaging is at the forefront of AI development, with growing applications and emerging challenges. Curriculum development in this area is crucial for getting the most out of this growing field and for taking advantage of the several knowledge gaps and development opportunities from medical school to cardiovascular diseases training programs.[143] Training statements from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recognize AI as a core competency across imaging modalities. At the same time, AI outputs remain imperfect, and trainees must be taught to independently review images, validate measurements, and recognize potential errors.[144]

AI is now routinely used in cardiology, including wearable devices that accurately detect common arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, with a recent meta-analysis reporting a pooled AUC of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.96–0.99).[145] These tools are well suited for screening and population-level prevention but are not diagnostic on their own. Clinical experience has shown that AI performance varies by task and patient population, showing the need for clinician oversight.[146] [147] Medical education must therefore train clinicians to actively interrogate AI outputs rather than accept them at face value. Trainees should learn to identify false-positive and false- negative results and to review interpretability outputs, such as saliency maps, to assess whether model attention aligns with physiologically meaningful ECG features before acting on AI-generated predictions.

6.2 Simulations and Skilled Assessment in Cardiovascular Diseases

Surgery and other procedural fields have adopted AI systems that use natural language processing and deep neural networks to track case exposure and acquired competencies during training. These tools can expand and refine competency classification, achieve accuracies up to 97%, and even suggest appropriate logging of complex cases based on procedural language.148 Similar systems would be highly applicable to interventional cardiology, electrophysiology, and structural heart training, where increasing procedural volume and complexity make manual tracking challenging. As cardiovascular therapies continue to evolve rapidly, AI may also support lifelong learning by facilitating ongoing competency assessment and credentialing.

In parallel, advances in portable, high-resolution recording devices now allow NLP-based tools to categorize and log procedures in near real time according to type and complexity.[149] This approach can provide timely, objective feedback to trainees, support completion of comprehensive training requirements, and enable program leadership to better individualize learning objectives and procedural opportunities.

CONCLUSIONS

Artificial intelligence has transformed traditional cardiovascular diagnostic tools into predictive systems capable of learning from clinical data. This shift requires a corresponding evolution in cardiovascular medical education toward personalized, precision-based, and high- fidelity training. Deep and convolutional neural networks have revitalized the electrocardiogram, expanding its role from pattern recognition to risk prediction and longitudinal assessment. In parallel, large language models and natural language processing now support multidisciplinary heart teams through clinical decision-support tools that also serve as educational platforms. Medical education has likewise advanced through the use of digital twins and AI-enhanced simulation, which improve procedural accuracy, learner confidence, and skill retention. To ensure safe and effective integration into practice, medical curricula must prioritize AI literacy and competency-based training. Preparing future clinicians to critically interpret and apply AI-supported insights will help bridge education with clinical care and support lifelong learning in an increasingly data-driven healthcare environment.

Key Terms

Machine Learning (ML)

A type of AI in which computers learn from data rather than following fixed rules.

Deep Learning

A form of machine learning that uses multiple layers of computation to detect complex patterns in images, signals, or text.

Deep Neural Network (DNN)

A deep learning model made of many connected layers that learns from large datasets to make predictions.

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

A specialized deep learning model designed to recognize patterns in images or signals, such as ECG waveforms or medical scans.

Digital Twin

A patient-specific virtual model of the body or an organ system that can be used to simulate how disease or treatments might affect that individual.

High-Fidelity Simulation

A realistic simulation that closely mimics real clinical conditions, including physiology and patient responses.

Risk Prediction (vs Diagnosis)

Diagnosis identifies what is happening now; risk prediction estimates the chance of developing a disease or outcome in the future.

Clinical Decision Support (AI-CDSS)

Software that uses AI to provide risk estimates or recommendations to help clinicians make decisions.

Large Language Model (LLM)

An AI system trained on large amounts of text that can understand and generate human-like language.

Natural Language Processing (NLP)

AI methods that extract meaning from written or spoken language, such as clinical notes.

Black Box Model

An AI system that gives a result (like a risk score) without clearly showing how it reached that conclusion.

Explainable AI (XAI)

AI methods that reveal why a model made a certain prediction, increasing transparency and trust.

Algorithmic Bias

When an AI system performs differently across groups because of differences in data or design.

Overreliance (Automation Bias)

The tendency to trust AI outputs too much, even when they may be wrong.

Deskilling

Loss of human expertise when clinicians rely too heavily on automated systems.

Extended Reality (XR)

Immersive technologies, including virtual and augmented reality, used for training and simulation.

Haptics

Technology that provides touch or force feedback, such as feeling resistance during a simulated procedure.

Latent Features

Hidden patterns in data that AI can detect even when they are not visible to humans

References

-

- Scientific Image and Illustration Software [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 31]. Available from: https://www.biorender.com/

- Sriram A, Ramachandran K, Krishnamoorthy S. Artificial intelligence in medical education: Transforming learning and practice. Cureus. 2025 Mar;17(3):e80852.

- Li J, Yin K, Wang Y, Jiang X, Chen D. Effectiveness of generative artificial intelligence-based teaching versus traditional teaching methods in medical education: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med Educ. 2025 Aug 19;25(1):1175.

- Ramsamooj A, Ibrahim SM, Gerriets VA, Cusick JK, Ramsamooj R. Artificial Intelligence versus traditional learning in a medical school setting. Cureus. 2025 Jun;17(6):e85262.

- Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Okatta AU, Amaechi EC, Elendu TC, Ezeh CP, et al. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024 Jul 5;103(27):e38813.

- Moradimokhles H, Hwang GJ, Zangeneh H, Pourjamshidi M, Hossein Amooeirazani A. Study of deep learning in medical education: Opportunities, achievements and future challenges. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2024 Jul;12(3):148–62.

- Toofaninejad E, Rezapour SM, Kalantarion M. Utilizing digital twins for the transformation of medical education. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2024 Apr;12(2):132–3.

- Mennella C, Maniscalco U, De Pietro G, Esposito M. Ethical and regulatory challenges of AI technologies in healthcare: A narrative review. Heliyon. 2024 Feb 29;10(4):e26297.

- Negri E, Fumagalli L, Macchi M. A review of the roles of digital twin in CPS-based production systems. Procedia Manuf. 2017;11:939–48.

- In healthcare, a digital twin is essentially a patient-specific digital replica of anatomy and physiology. Unlike static simulations, digital twins continuously integrate real-time data (e.g. from electronic health records or wearables) to update the model’s state.

- Randles A. Digital Twins in Healthcare: Revolutionizing Patient Care at Duke [Internet]. Center for Computational and Digital Health Innovation. 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 19]. Available from: https://comphealth.duke.edu/digital-twins-in-healthcare-revolutionizing-patient-care-at-duke/#:~:text=Unlike%20static%20computational%20models%2C%20digital,the%20patient%E2%80%99s%20specific%20health%20profile

- Sadée C, Testa S, Barba T, Hartmann K, Schuessler M, Thieme A, et al. Medical digital twins: enabling precision medicine and medical artificial intelligence. Lancet Digit Health. 2025 Jul;7(7):100864.

- Yang W, Shen S, Yang D, Yu S, Yao Z, Cao S. Digital twin applications in medical education: A scoping review. Education Science and Management. 2024 Dec 17;2(4):188–96.

- Rovati L, Gary PJ, Cubro E, Dong Y, Kilickaya O, Schulte PJ, et al. Development and usability testing of a patient digital twin for critical care education: a mixed methods study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1336897.

- Halpern GA, Nemet M, Gowda DM, Kilickaya O, Lal A. Advances and utility of digital twins in critical care and acute care medicine: a narrative review. J Yeungnam Med Sci. 2025;42:9.

- Li H, Zhang J, Zhang N, Zhu B. Advancing emergency care with digital twins. JMIR Aging. 2025 Apr 21;8:e71777.

- Wang M, Hu H, Wu S. Opportunities and challenges of digital twin technology in healthcare. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023 Dec 5;136(23):2895–6.

- Peshkova M, Yumasheva V, Rudenko E, Kretova N, Timashev P, Demura T. Digital twin concept: Healthcare, education, research. J Pathol Inform. 2023 Apr 16;14(100313):100313.

- Zackoff MW, Rios M, Davis D, Boyd S, Roque I, Anderson I, et al. Immersive virtual reality onboarding using a digital twin for a new clinical space expansion: A novel approach to large-scale training for health care providers. J Pediatr. 2023 Jan;252:7–10.e3.

- Zackoff MW, Davis D, Rios M, Sahay RD, Zhang B, Anderson I, et al. Tolerability and acceptability of autonomous immersive virtual reality incorporating digital twin technology for mass training in healthcare. Simul Healthc. 2024 Oct 1;19(5):e99–116.

- Mekki YM, Luijten G, Hagert E, Belkhair S, Varghese C, Qadir J, et al. Digital twins for the era of personalized surgery. NPJ Digit Med. 2025 May 15;8(1):283.

- Zhao F, Wu Y, Hu M, Chang CW, Liu R, Qiu R, et al. Current progress of digital twin construction using medical imaging. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2025 Sep;26(9):e70226.

- Khoshfekr Rudsari H, Tseng B, Zhu H, Song L, Gu C, Roy A, et al. Digital twins in healthcare: a comprehensive review and future directions. Front Digit Health. 2025 Nov 18;7(1633539):1633539.

- Zhang K, Zhou HY, Baptista-Hon DT, Gao Y, Liu X, Oermann E, et al. Concepts and applications of digital twins in healthcare and medicine. Patterns (N Y). 2024 Aug 9;5(8):101028.

- Sel K, Osman D, Zare F, Masoumi Shahrbabak S, Brattain L, Hahn JO, et al. Building digital twins for cardiovascular health: From principles to clinical impact. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024 Oct;13(19):e031981.

- Xie H, Huang Q, Yu H, Qu Y, Yuan M, Wu H, et al. Digital twin for atrial fibrillation: fundamentals, current advances, challenges and future perspectives. Inf Fusion. 2026 Apr;128(103957):103957.

- Trayanova NA, Prakosa A. Up digital and personal: How heart digital twins can transform heart patient care. Heart Rhythm. 2024 Jan;21(1):89–99.

- Kumar A, Saudagar AKJ, Khan MB. Enhanced medical education for physically disabled people through integration of IoT and digital twin technologies. Systems. 2024 Aug 26;12(9):325.

- Pandey PK, Mahajan S, Pandey PK, Paul J, Iyer S. Immersive learning trends using digital twins. In: Digital Twins for Smart Cities and Villages. Elsevier; 2025. p. 249–71.

- Hassani H, Huang X, MacFeely S. Impactful digital twin in the healthcare revolution. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2022 Aug 8;6(3):83.

- Asciak L, Kyeremeh J, Luo X, Kazakidi A, Connolly P, Picard F, et al. Digital twin assisted surgery, concept, opportunities, and challenges. NPJ Digit Med. 2025 Jan 15;8(1):32.

- Zhang J, Zhu J, Tu W, Wang M, Yang Y, Qian F, et al. The effectiveness of a digital twin learning system in assisting engineering education courses: A case of landscape architecture. Appl Sci (Basel). 2024 Jul 25;14(15):6484.

- Ainakulov Z, Koshekov K, Astapenko N, Pirmanov I, Koshekov A. The experience of introducing digital twins into the educational process on the example of training in the repair of aircraft equipment units. J Theor Appl Inf Technol [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 20]; Available from: https://www.jatit.org/volumes/Vol101No12/24Vol101No12.pdf

- Silva A, Vale N. Digital Twins in personalized medicine: Bridging innovation and clinical reality. J Pers Med. 2025 Oct 22;15(11):503.

- Papachristou K, Katsakiori PF, Papadimitroulas P, Strigari L, Kagadis GC. Digital Twins’ advancements and applications in healthcare, towards precision medicine. J Pers Med. 2024 Nov 11;14(11):1101.

- Akbarialiabad H, Pasdar A, Murrell DF, Mostafavi M, Shakil F, Safaee E, et al. Enhancing randomized clinical trials with digital twins. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2025 Oct 3;11(1):110.

- Saratkar SY, Langote M, Kumar P, Gote P, Weerarathna IN, Mishra GV. Digital twin for personalized medicine development. Front Digit Health. 2025 Aug 7;7:1583466.

- Ringeval M, Etindele Sosso FA, Cousineau M, Paré G. Advancing health care with digital twins: Meta-review of applications and implementation challenges. J Med Internet Res. 2025 Feb 19;27:e69544.

- Pathak DRK, Upadhyay DP. Integration of digital twins technologies in education for experiential learning: Benefits and challenges. Int Res J Adv Engg Hub. 2024 Mar 16;2(03):442–9.

- Sel K, Hawkins-Daarud A, Chaudhuri A, Osman D, Bahai A, Paydarfar D, et al. Survey and perspective on verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification of digital twins for precision medicine. NPJ Digit Med. 2025 Jan 17;8(1):40.

- Hua EY, Lazarova-Molnar S, Francis DP. Validation of digital twins: Challenges and opportunities. In: 2022 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC). IEEE; 2022. p. 2900–11.

- Attia ZI, Noseworthy PA, Lopez-Jimenez F, Asirvatham SJ, Deshmukh AJ, Gersh BJ, et al. An artificial intelligence-enabled ECG algorithm for the identification of patients with atrial fibrillation during sinus rhythm: a retrospective analysis of outcome prediction. Lancet. 2019 Sep 7;394(10201):861–7.

- Attia ZI, Kapa S, Lopez-Jimenez F, McKie PM, Ladewig DJ, Satam G, et al. Screening for cardiac contractile dysfunction using an artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiogram. Nat Med. 2019 Jan;25(1):70–4.

- Sau A, Pastika L, Sieliwonczyk E, Patlatzoglou K, Ribeiro AH, McGurk KA, et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiogram for mortality and cardiovascular risk estimation: a model development and validation study. Lancet Digit Health. 2024 Nov;6(11):e791–802.

- Lee MS, Shin TG, Lee Y, Kim DH, Choi SH, Cho H, et al. Artificial intelligence applied to electrocardiogram to rule out acute myocardial infarction: the ROMIAE multicentre study. Eur Heart J. 2025 May 21;46(20):1917–29.

- Moon J, Kim JH, Hong SJ, Yu CW, Kim YH, Kim EJ, et al. Deep learning model for identifying acute heart failure patients using electrocardiography in the emergency room. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2025 Feb 20;14(2):74–82.

- Liu WT, Hsieh PH, Lin CS, Fang WH, Wang CH, Tsai CS, et al. Opportunistic screening for asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction with the use of electrocardiographic artificial intelligence: A cost-effectiveness approach. Can J Cardiol. 2024 Jul;40(7):1310–21.

- Adedinsewo DA, Morales-Lara AC, Afolabi BB, Kushimo OA, Mbakwem AC, Ibiyemi KF, et al. Artificial intelligence guided screening for cardiomyopathies in an obstetric population: a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Nat Med. 2024 Oct;30(10):2897–906.

- Liu WT, Lin C, Lee CC, Chang CH, Fang WH, Tsai DJ, et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled ECGs for atrial fibrillation identification and enhanced oral anticoagulant adoption: A pragmatic randomized clinical trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025 Jul 15;14(14):e042106.

- Lin CS, Liu WT, Tsai DJ, Lou YS, Chang CH, Lee CC, et al. AI-enabled electrocardiography alert intervention and all-cause mortality: a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Nat Med. 2024 May;30(5):1461–70.

- Tsai DJ, Lin C, Liu WT, Lee CC, Chang CH, Lin WY, et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted diagnosis and prognostication in low ejection fraction using electrocardiograms in inpatient department: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2025 Jun 9;23(1):342.

- Ferreira ALC, Feitoza LPG de C, Benitez ME, Aziri B, Begic E, de Souza LVF, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of artificial-intelligence-based electrocardiogram algorithm to estimate heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2025 Apr;50(4):103004.

- Popat A, Saini B, Patel M, Seby N, Patel S, Harikrishnan S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of AI algorithms in aortic stenosis screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Med Res. 2024 Sep;22(3):145–55.

- Mayourian J, Asztalos IB, El-Bokl A, Lukyanenko P, Kobayashi RL, La Cava WG, et al. Electrocardiogram-based deep learning to predict left ventricular systolic dysfunction in paediatric and adult congenital heart disease in the USA: a multicentre modelling study. Lancet Digit Health. 2025 Apr;7(4):e264–74.

- Surendra K, Nürnberg S, Bremer JP, Knorr MS, Ückert F, Wenzel JP, et al. Pragmatic screening for heart failure in the general population using an electrocardiogram-based neural network. ESC Heart Fail. 2023 Apr;10(2):975–84.

- Gupta MD, Goyal D, Kunal S, Shetty MK, Girish MP, Batra V, et al. Comparative evaluation of machine learning models versus TIMI score in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients. Indian Heart J. 2025 May;77(3):133–41.

- Hao Y, Tan NKW, Gao EY, Au JXY, Toh NEX, Yong CL, et al. Electrocardiogram heart rate variability for machine learning diagnosis of obstructive sleep Apnoea: A bayesian meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2025 Sep 30;29(5):303.

- Hill NR, Arden C, Beresford-Hulme L, Camm AJ, Clifton D, Davies DW, et al. Identification of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation patients using a machine learning risk prediction algorithm and diagnostic testing (PULsE-AI): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020 Dec;99(106191):106191.

- Zaboli A, Brigo F, Ziller M, Massar M, Parodi M, Magnarelli G, et al. Exploring ChatGPT’s potential in ECG interpretation and outcome prediction in emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2025 Feb;88:7–11.

- Günay S, Öztürk A, Yiğit Y. The accuracy of Gemini, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in ECG analysis: A comparison with cardiologists and emergency medicine specialists. Am J Emerg Med. 2024 Oct;84:68–73.

- Avidan Y, Tabachnikov V, Court OB, Khoury R, Aker A. In the face of confounders: Atrial fibrillation detection – Practitioners vs. ChatGPT. J Electrocardiol. 2025 Jan;88(153851):153851.

- Gupta MD, Bansal A, Sarkar PG, Girish MP, Jha M, Yusuf J, et al. Design and rationale of an intelligent algorithm to detect BuRnoUt in HeaLthcare workers in COVID era using ECG and artificiaL intelligence: The BRUCEE-LI study. Indian Heart J. 2021 Jan;73(1):109–13.

- Shroyer S, Mehta S, Thukral N, Smiley K, Mercaldo N, Meyers HP, et al. Accuracy of cath lab activation decisions for STEMI-equivalent and mimic ECGs: Physicians vs. AI (Queen of Hearts by PMcardio). Am J Emerg Med. 2025 Nov;97:193–9.

- Natali C, Marconi L, Dias Duran LD, Cabitza F. AI-induced deskilling in medicine: A mixed-method review and research agenda for healthcare and beyond. Artif Intell Rev [Internet]. 2025 Aug 27;58(11). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10462-025-11352-1

- Poon AIF, Sung JJY. Opening the black box of AI-Medicine. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Mar;36(3):581–4.

- Tuan DA. Bridging the gap between black box AI and clinical practice: Advancing explainable AI for trust, ethics, and personalized healthcare diagnostics [Internet]. Preprints. 2024. Available from: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202409.1974

- Mehta N, Mehta S, Rubenstein A, Wood SK. Not replaced, but reinvented: AI education pathways to prepare future physicians to lead healthcare transformation. Perspect Med Educ. 2025 Nov 21;14(1):849–59.

- Lampropoulos G. Augmented reality, virtual reality, and intelligent tutoring systems in education and training: A systematic literature review. Appl Sci (Basel). 2025 Mar 15;15(6):3223.

- Kumar A, Saudagar AKJ, Kumar A, Alkhrijah YM, Raja L. Innovating medical education using a cost effective and scalable VR platform with AI-Driven haptics. Sci Rep. 2025 Jul 20;15(1):26360.

- Strojny P, Dużmańska-Misiarczyk N. Measuring the effectiveness of virtual training: A systematic review. Computers & Education: X Reality. 2023;2(100006):100006.

- Lin H, Chen Q. Artificial intelligence (AI) -integrated educational applications and college students’ creativity and academic emotions: students and teachers’ perceptions and attitudes. BMC Psychol. 2024 Sep 16;12(1):487.

- Zertuche JP, Connors J, Scheinman A, Kothari N, Wong K. Using virtual reality as a replacement for hospital tours during residency interviews. Med Educ Online. 2020 Jan 1;25(1):1777066.

- Garber AM, Meliagros P, Diener-Brazelle J, Dow A. Using virtual reality to teach medical students cross-coverage skills. Am J Med. 2024 May;137(5):454–8.

- Riddle EW, Kewalramani D, Narayan M, Jones DB. Surgical simulation: Virtual reality to artificial intelligence. Curr Probl Surg. 2024 Nov;61(11):101625.

- Mergen M, Graf N, Meyerheim M. Reviewing the current state of virtual reality integration in medical education – a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Jul 23;24(1):788.

- Vittadello A, Savino S, Bressan S, Costa M, Boscolo A, Sella N, et al. Virtual reality for training emergency medicine residents in emergency scenarios: usefulness of a tutorial to enhance the simulation experience. Front Digit Health. 2025 Feb 18;7:1466866.

- Lin SJ, Chang CJ, Chu SC, Chang YH, Hong MY, Huang PC, et al. Investigating BLS instructors’ ability to evaluate CPR performance: focus on compression depth, rate, and recoil. BMC Emerg Med. 2025 Jan 29;25(1):19.

- Emami P, Sistani M, Marzban A. The future of CPR: Leveraging artificial intelligence for enhanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcomes. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2024 Apr;19(2):77–8.

- Laerdal Manikins [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.pocketnurse.com/default/products/laerdal-manikins/laerdal-low-fidelity-manikins

- Abhinaw. How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing CPR and First Aid [Internet]. Online CPR Certification. American Healthcare Academy; 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 20]. Available from: https://cpraedcourse.com/blog/artificial-intelligence-in-cpr

- Augusto JB, Santos MB, Faria D, Alves P, Roque D, Morais J, et al. Real-time visual feedback device improves quality of chest compressions: A manikin study. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2020 Jul;8(3):135–41.

- Hyun Choi D, Ha Joo Y, Hong Kim K, Ho Park J, Joo H, Kong HJ, et al. A development of a sound recognition-based cardiopulmonary resuscitation training system. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2024 Jul 29;12:550–7.

- Baldi E, Cornara S, Contri E, Epis F, Fina D, Zelaschi B, et al. Real-time visual feedback during training improves laypersons’ CPR quality: a randomized controlled manikin study. CJEM. 2017 Nov;19(6):480–7.

- Berg KM, Bray JE, Ng KC, Liley HG, Greif R, Carlson JN, et al. 2023 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary from the basic life support; Advanced life support; Pediatric life support; Neonatal life support; Education, implementation, and teams; And first aid task forces. Circulation. 2023 Dec 12;148(24):e187–280.

- Schipper AE, Sloane CSM, Shimelis LB, Kim RT. Technological innovations in layperson CPR education – A scoping review. Resusc Plus. 2025 May;23(100924):100924.

- García Fierros FJ, Moreno Escobar JJ, Sepúlveda Cervantes G, Morales Matamoros O, Tejeida Padilla R. VirtualCPR: Virtual reality mobile application for training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques. Sensors (Basel). 2021 Apr 3;21(7):2504.

- Red Cross Training & Certification, and Store [Internet]. Red Cross. [cited 2025 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.redcross.org/take-a-class/organizations/smart?srsltid=AfmBOor7QQYRRHdTboTCIAHuZzqP5COfZHS8TSuqKe5udPnKmvtYSiB0

- American Red Cross Introduces New ElevateTM SMART Manikin Training Solution That Delivers Enhanced Precision and Expansive Reach [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.redcross.org/about-us/news-and-events/press-release/2024/american-red-cross-introduces-new-elevate-SMART-manikin-training-solution-that-delivers-enhanced-precision-and-expansive-reach.html?srsltid=AfmBOorzYr1wOs6ilH2rluhrdS4oYFAFcUJvrLtlFJ3katsaxOSg5nEi

- CPR in Schools® With First Aid Training Kits [Internet]. cpr.heart.org. [cited 2025 Dec 20]. Available from: https://cpr.heart.org/en/courses/cpr-in-schools-training-kits

- Nicolau A, Jorge I, Vieira-Marques P, Sa-Couto C. Influence of training with corrective feedback devices on cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills acquisition and retention: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Med Educ. 2024 Dec 19;10:e59720.

- Medical students use AI to practice communication skills [Internet]. Cornell Bowers. [cited 2025 Dec 20]. Available from: https://bowers.cornell.edu/news-stories/medical-students-use-ai-practice-communication-skills

- Telehealth Training for Nursing Students Using AI Simulations – European Society of Medicine [Internet]. European Society of Medicine -. European Society of Medicine; 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 20]. Available from: https://esmed.org/telehealth-training-for-nursing-students-using-ai-simulations

- Raquepo TM, Tobin M, Puducheri S, Yamin M, Dhillon J, Bridgeman M, et al. Artificial intelligence in microsurgical education: A systematic review of its role in training surgeons. J Reconstr Microsurg [Internet]. 2025 Aug 14; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/a-2672-0260

- Farooq F, Warraich MUT, Ud Din MM, Saleem N, Asif MS, Khan H. Role of artificial intelligence in gastroenterology training (2005-2025): Trends, tools, and challenges. Cureus. 2025 Aug;17(8):e90085.

- Bhakar R, Miller J, Simenacz A. Artificial intelligence and surgical education in the UK: A systematic review of current use, evidence gaps and future directions. Cureus. 2025 Dec;17(12):e98231.

- Ng ZX, Ng IW, Tan TH. Enhancing radiation oncology education through artificial intelligence: A review of applications, limitations, and future directions. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. 2025 Oct 18; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13187-025-02763-3

- Pan W, Li S, Tian B, Zheng Y, Wang H. Artificial intelligence in medical education for pulmonary nodule management: a narrative review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2025 Sep 30;14(9):4068–77.

- Escobar-Castillejos D, Barrera-Animas AY, Noguez J, Magana AJ, Benes B. Transforming surgical training with AI techniques for training, assessment, and evaluation: Scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2025 Nov 18;27:e58966.

- Li Z, Shi L, Pei M, Chen W, Tang Y, Qiu G, et al. DeepSeek-AI-enhanced virtual reality training for mass casualty management: Leveraging machine learning for personalized instructional optimization. PLoS One. 2025 Jun 11;20(6):e0321352.

- Borg A, Schiött J, Ivegren W, Gentline C, Huss V, Hugelius A, et al. AI-enhanced social robotic versus computer-based virtual patients for clinical reasoning training in medical education: Observational crossover cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2025 Nov 27;27:e82541.

- Truong H, Qi D, Ryason A, Sullivan AM, Cudmore J, Alfred S, et al. Does your team know how to respond safely to an operating room fire? Outcomes of a virtual reality, AI-enhanced simulation training. Surg Endosc. 2022 May;36(5):3059–67.

- Fazlollahi AM, Yilmaz R, Winkler-Schwartz A, Mirchi N, Ledwos N, Bakhaidar M, et al. AI in surgical curriculum design and unintended outcomes for technical competencies in simulation training. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Sep 5;6(9):e2334658.

- Lan M, Zhou X. A qualitative systematic review on AI empowered self-regulated learning in higher education. NPJ Sci Learn. 2025 May 3;10(1):21.

- Kovari A. AI Gem: Context-aware transformer agents as digital twin tutors for adaptive learning. Computers. 2025 Sep 2;14(9):367.

- Cheng A, McGregor C. Applications of artificial intelligence in healthcare simulation: a model of thinking. Adv Simul (Lond). 2025 Sep 18;10(1):45.

- Zidoun Y, Mardi AE. Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Based simulators versus simulated patients in undergraduate programs: A protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Nov 5;24(1):1260.

- Peralta Ramirez AA, Trujillo López S, Navarro Armendariz GA, De la Torre Othón SA, Sierra Cervantes MR, Medina Aguirre JA. Clinical simulation with ChatGpt: A revolution in medical education? J CME. 2025 Jun 27;14(1):2525615.

- Savino S, Mormando G, Saia G, Da Dalt L, Chang TP, Bressan S. SIMPEDVR: using VR in teaching pediatric emergencies to undergraduate students-a pilot study. Eur J Pediatr. 2024 Jan;183(1):499–502.

- Fernández-Arias P, del Bosque A, Lampropoulos G, Vergara D. Applications of AI and VR in high-risk training simulations: A bibliometric review. Appl Sci (Basel). 2025 May 13;15(10):5424.

- Ren X. From German innovation to Chinese application: AI/VR strategies for medical education in underdeveloped regions. In: 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Education (ICAIE). IEEE; 2025. p. 546–50.

- Veenhuizen M, O’Malley A. Demographic biases in AI-generated simulated patient cohorts: a comparative analysis against census benchmarks. Adv Simul (Lond). 2025 Nov 18;10(1):58.

- Fung TCJ, Chan SL, Lam CFM, Lam CY, Cheng CCW, Lai MH, et al. Effects of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) patient simulation on perceived clinical competency among global nursing undergraduates: a cross-over randomised controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 2025 Jul 17;24(1):934.

- Conigliaro RL, Peterson KD, Stratton TD. Lack of diversity in simulation technology: An educational limitation?: An educational limitation? Simul Healthc. 2020 Apr;15(2):112–4.

- Shahrezaei A, Sohani M, Taherkhani S, Zarghami SY. The impact of surgical simulation and training technologies on general surgery education. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Nov 13;24(1):1297.

- Turbanova UV, Salimova ZU. Ethical and legal considerations in simulation-based medical training [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 20]. Available from: https://webofjournals.com/index.php/5/article/download/3536/3496

- Farouk AM, Naganathan H, Rahman RA, Kim J. Exploring the economic viability of virtual reality in architectural, engineering, and construction education. Buildings. 2024 Aug 27;14(9):2655.

- Baniasadi T, Ayyoubzadeh SM, Mohammadzadeh N. Challenges and practical considerations in applying virtual reality in medical education and treatment. Oman Med J. 2020 May;35(3):e125.

- Saredakis D, Szpak A, Birckhead B, Keage HAD, Rizzo A, Loetscher T. Factors associated with virtual reality sickness in head-mounted displays: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020 Mar 31;14(96):96.

- Biswas N, Mukherjee A, Bhattacharya S. “Are you feeling sick?” – A systematic literature review of cybersickness in virtual reality. ACM Comput Surv. 2024 Nov 30;56(11):1–38.

- Lüscher TF, Wenzl FA, D’Ascenzo F, Friedman PA, Antoniades C. Artificial intelligence in cardiovascular medicine: clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2024 Oct 21;45(40):4291–304.

- Parsa S, Somani S, Dudum R, Jain SS, Rodriguez F. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Is it Ready for Prime Time? Curr Atheroscler Rep. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2024 Jul;26(7):263–72.

- Li A, Wang Y, Chen H. AI driven cardiovascular risk prediction using NLP and Large Language Models for personalized medicine in athletes. SLAS Technol. 2025 Jun;32(100286):100286.

- Kotanidis CP, Xie C, Alexander D, Rodrigues JCL, Burnham K, Mentzer A, et al. Constructing custom-made radiotranscriptomic signatures of vascular inflammation from routine CT angiograms: a prospective outcomes validation study in COVID-19. Lancet Digit Health. 2022 Oct;4(10):e705–16.

- Wu J, Biswas D, Ryan M, Bernstein BS, Rizvi M, Fairhurst N, et al. Artificial intelligence methods for improved detection of undiagnosed heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024 Feb;26(2):302–10.

- Choi DJ, Park JJ, Ali T, Lee S. Artificial intelligence for the diagnosis of heart failure. NPJ Digit Med. 2020 Apr 8;3(1):54.

- Tu T, Palepu A, Schaekermann M, Saab K, Freyberg J, Tanno R, et al. Towards Conversational Diagnostic AI [Internet]. arXiv [cs.AI]. 2024. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.05654

- Lin C, Kuo CF. Roles and potential of Large language models in healthcare: A comprehensive review. Biomed J. 2025 Oct;48(5):100868.

- Sudri K, Motro-Feingold I, Ramon-Gonen R, Barda N, Klang E, Fefer P, et al. Enhancing coronary revascularization decisions: The promising role of large language models as a decision-support tool for multidisciplinary heart team. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024 Nov;17(11):e014201.

- Garin D, Cook S, Ferry C, Bennar W, Togni M, Meier P, et al. Improving large language models accuracy for aortic stenosis treatment via Heart Team simulation: a prompt design analysis. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2025 Jul;6(4):665–74.

- Bergmann D. What Is Deep Learning? [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 21]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/deep-learning

- Hannun AY, Rajpurkar P, Haghpanahi M, Tison GH, Bourn C, Turakhia MP, et al. Publisher Correction: Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network. Nat Med. 2019 Mar;25(3):530.

- Papetti DM, Van Abeelen K, Davies R, Menè R, Heilbron F, Perelli FP, et al. An accurate and time-efficient deep learning-based system for automated segmentation and reporting of cardiac magnetic resonance-detected ischemic scar. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2023 Feb;229(107321):107321.

- Hannun AY, Rajpurkar P, Haghpanahi M, Tison GH, Bourn C, Turakhia MP, et al. Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network. Nat Med. 2019 Jan;25(1):65–9.

- van de Leur RR, Blom LJ, Gavves E, Hof IE, van der Heijden JF, Clappers NC, et al. Automatic triage of 12-lead ECGs using deep convolutional neural networks. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 May 18;9(10):e015138.

- Fiorina L, Maupain C, Gardella C, Manenti V, Salerno F, Socie P, et al. Evaluation of an ambulatory ECG analysis platform using deep neural networks in routine clinical practice. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022 Sep 20;11(18):e026196.

- Gumpfer N, Grün D, Hannig J, Keller T, Guckert M. Detecting myocardial scar using electrocardiogram data and deep neural networks. Biol Chem. 2021 Jul 27;402(8):911–23.

- Ríos-Muñoz GR, Fernández-Avilés F, Arenal Á. Convolutional neural networks for mechanistic driver detection in atrial fibrillation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 11;23(8):4216.

- Stephens AF, Šeman M, Diehl A, Pilcher D, Barbaro RP, Brodie D, et al. ECMO PAL: using deep neural networks for survival prediction in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 2023 Sep;49(9):1090–9.

- Weimann K, Conrad TOF. Federated learning with deep neural networks: A privacy-preserving approach to enhanced ECG classification. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2024 Nov;28(11):6931–43.

- Gogin N, Viti M, Nicodème L, Ohana M, Talbot H, Gencer U, et al. Automatic coronary artery calcium scoring from unenhanced-ECG-gated CT using deep learning. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2021 Nov;102(11):683–90.

- Samant S, Bakhos JJ, Wu W, Zhao S, Kassab GS, Khan B, et al. Artificial intelligence, computational simulations, and extended reality in cardiovascular interventions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023 Oct 23;16(20):2479–97.

- Çalışkan SA, Demir K, Karaca O. Artificial intelligence in medical education curriculum: An e-Delphi study for competencies. Sattar K, editor. PLOS ONE. 2022 Jul 21;17.

- Civaner MM, Uncu Y, Bulut F, Chalil EG, Tatlı A. Artificial intelligence in medical education: A cross-sectional needs assessment [Internet]. Research Square. 2022. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1612566/v1

- Writing Committee Members, Baldassarre LA, Mendes LA, Blankstein R, Hahn RT, Patel AR, et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCCT/SCMR advanced training statement on advanced cardiovascular imaging: A report of the ACC competency management committee. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2025 Dec;18(12):1120.

- Barrera N, Solorzano M, Jimenez Y, Kushnir Y, Gallegos-Koyner F, Dagostin de Carvalho G. Accuracy of smartwatches in the detection of atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. JACC Adv. 2025 Nov;4(11 Pt 1):102133.

- Jackson P, Ponath Sukumaran G, Babu C, Tony MC, Jack DS, Reshma VR, et al. Artificial intelligence in medical education – perception among medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Jul 27;24(1):804.

- Boonstra MJ, Weissenbacher D, Moore JH, Gonzalez-Hernandez G, Asselbergs FW. Artificial intelligence: revolutionizing cardiology with large language models. Eur Heart J. 2024 Feb 1;45(5):332–45.

- Gordon M, Daniel M, Ajiboye A, Uraiby H, Xu NY, Bartlett R, et al. A scoping review of artificial intelligence in medical education: BEME Guide No. 84. Med Teach. 2024 Apr;46(4):446–70.

- Kawka M, Gall TMH, Fang C, Liu R, Jiao LR. Intraoperative video analysis and machine learning models will change the future of surgical training. Intelligent Surgery. 2022 Jan;1:13–5.

Ashlesha Chaudhary, MBBS

Ashlesha Chaudhary, MBBS, is a first-year Internal Medicine resident at Bassett Healthcare Network, Cooperstown, New York.

She completed her medical training in Nepal and has interests in cardiovascular medicine and clinical research.

Carlos Espiche-Salazar, MD, MEd

Carlos Espiche-Salazar, MD, MEd, is a Peruvian-trained physician who completed his internal medicine residency at Saint Barnabas Hospital in New York and currently practices at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. He is an incoming Cardiovascular Disease Fellow at Bassett Healthcare Network.

Andrew Krumerman, MD

Andrew Krumerman, MD, is the Chair of Cardiology for Northwell’s Northern Westchester and Phelps Hospitals. He is Professor of Medicine at The Zucker School of Medicine. A leading specialist in catheter ablation for cardiac arrhythmias, he has published extensively on disparities in health care and the use of artificial intelligence to improve cardiac healthcare delivery. He co-developed the Pacer ID application, which allows for rapid identification of an implanted device manufacturer based on chest X-ray imaging [https://www.northwell.edu/imaging/services/x-ray].

Daniel Katz, MD

Daniel Katz is the Cardiovascular Disease Fellowship Program Director and Director of Cardiac MRI at Bassett Healthcare. His professional interests include emerging innovations in medical education, advances in cardiovascular disease and the evolving role of artificial intelligence

in clinical care and training. He has numerous publications on a variety of topics in cardiovascular disease including cardiovascular imaging, clinical cardiology and novel biomarkers. Dr. Katz is board certified in Cardiovascular Disease, Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology, Echocardiography and Cardiovascular MRI.